This week before Christmas, lyrics of carols repeat in our heads when we are walking into churches, department stores, or the lobby of my athletic club. Rightfully called ear worms some pursue us like demons to expel our sins of the year. Penance: Ten repetitions of The Little Drummer Boy. There may be no other holiday abounding in so much song as Christmas. Think of it. How many Valentine’s Day songs do you sing throughout February? I love the carols I learned as a child and play every December, either on recordings or my hesitant playing on my piano. Seventy to eighty years are adequate to retain the lyrics even if sung only one month of the year. The melodies are harmonious and, with a few exceptions, notes within a close pitch so I can sing along with minimal straining.

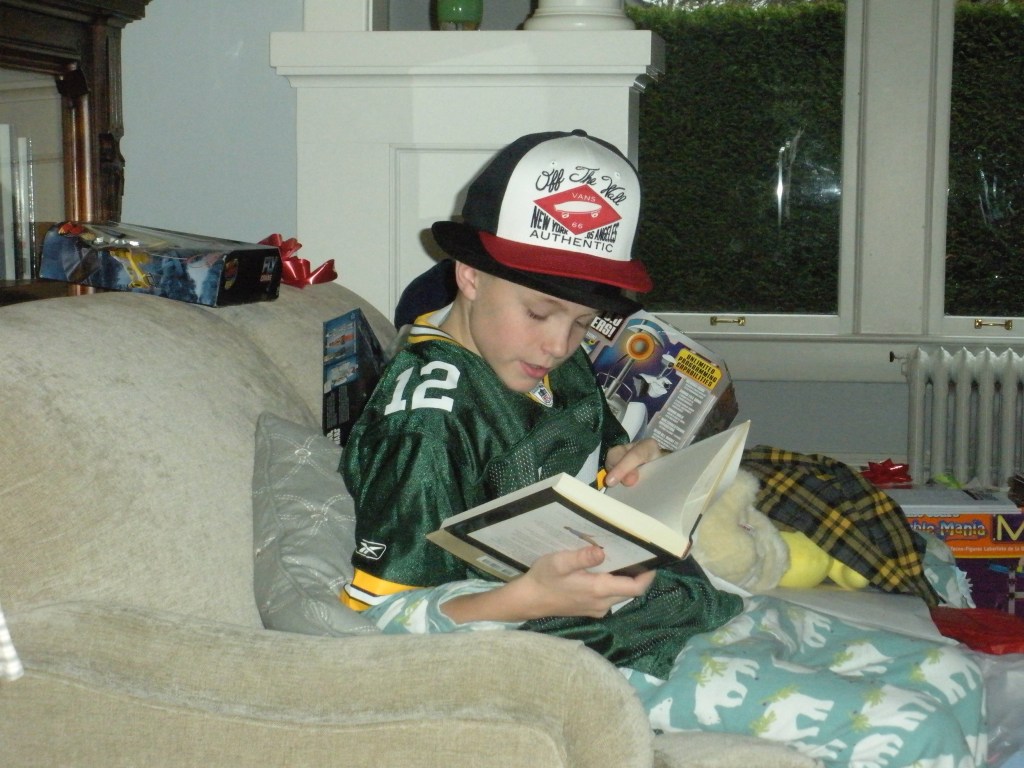

Singing along is best because almost everyone else knows the carols as well. Each year Pacific Lutheran University’s renown Choir of the West performs a Christmas Concert at Benaroya Hall, home of the Seattle Symphony. Two hundred college choir members walk down parallel aisles holding lit candles before ascending the steps to the stage. There they move into risers as gracefully as swimming swans. And all around their voices, accompanied by the orchestra, fill the hall with celebratory sound. After every three or four pieces sung by the choir, the conductor turns to the audience, waving us to join in on a familiar carol. We all rise as one, and we sing and SING and SING. The song might be Joy to the World, and it might not, but JOY overwhelms me as I sing familiar songs with as much choral gusto as I can summon. Surrounded by several hundred voices, who will recognize my strained, untutored voice? I feel marvelous. I feel proud when I can get through two verses without having to read the printed lyrics. This is MY music, My heritage. By the second verses, I am back in the children’s choir of a small white Congregational Church in Massachusetts.

After all those vocal trips to the manger, this year I am focusing more on the lyrics. Many were originally poems, later adapted to music. Because I am often captured by a phrase and held until I thoroughly hold it to the light of thought, my earworm this Christmas is not melody but verse. Over and over, I recite The Weary World Rejoices. In 1843, I learned, Placide Cappeau, wrote the poem O Holy Night in a commission to write something to celebrate the opening of new church in Fance. Later, the French composer of operas, Adolphe Adam in 1847, set the poem to music.

O holy night, the stars are brightly shining,

It is the night of the dear Savior’s birth;

Long lay the world in sin and error pining,

‘Till he appeared and the soul felt its worth.

A thrill of hope the weary world rejoices,

For yonder breaks a new and glorious morn;

Now I know the dates of the original, I wonder what was happening in France in the 1840’s to include the phrase, “the weary world,” as if anyone reading the poem would agree that the world is exhausted. I intuit that the 1840’s in France were similarly stressed as we are in America today. Still the richest country in the world, if the news is to be believed, Americans are struggling with their finances and their values. I don’t need the news to tell me that there is such political division in our country that we are exhausted hearing the latest shocking event coming out of the nation’s capitol. I have friends who, in an effort to shield their mental health, no longer listen to the news on television. I walk cautiously around lifelong friends who have political beliefs I know are contrary to my own. Will I engage them in debate? No way. I am just too exhausted.

Yet there is O Holy Night that acknowledges the world’s weariness as a backdrop for rejoicing. There in the birth of a messiah is a thrill of hope. Here the day before Christmas, I am rereading the many holiday cards sending greetings our way. The most common phrase is Merry Christmas, but this year, I am finding another word often repeating. It is hope. Such an abstract word. Out there like a thin line of ground fog on a winter morning is hope. We can’t earn it or buy it. Emily Dickinsen wrote Hope is the thing with feathers/That perches in the soul,/And sings the tune without the words,/And never stops at all. There it is, I notice hope and rejoicing more when the world is weary.

Perhaps this season, when so much seems uncertain, when many Americans feel their voices are not heard. we are more aware than in certain times of the promise of a Messiah. So much better than putting our money in a lottery. Like Emily’s bird flying against a storm, we are singing, if only the tune without the words. I find comfort in the community of carolers. I hope you will sing along.