“Hope” is the thing with feathers –

That perches in the soul –

And sings the tune without the words –

And never stops – at all

And sweetest – in the Gale – is heard –

And sore must be the storm –

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm –

I’ve heard it in the chillest land –

And on the strangest Sea –

Yet – never – in Extremity,

It asked a crumb – of me.

Emily Dickinson

Hope is the first green-gold bud of spring on winter’s leafless limbs. To have a word for hope is a miraculous thing, for how else could we express the force that inspires us to move forward in times of despair? Some linguists argue that without a word for an emotion, you can’t express, maybe not even feel the emotion. I disagree, but I understand the clarity that comes with being able to say, “I hope…”

Hope is not expectation, the latter assuming some planning and reasonable certainty. For example, we wait to plant lettuces until the last frost has passed so we may, according to the seed package, expectabundant produce in 58 days. Hope ,on the other hand, takes over as a word of the imagination, so we plant in April’s cool earth, regardless of knowing there could be more frosts, even snow or ice. Nevertheless, I press the seeds, little flecks, into the cool, damp soil while I imagine June’s salad.

Because it is a word of the imagination, hope reaches for the poet’s tools – simile and metaphor. Emily Dickinson writes “Hope is a thing with feathers that perches in the soul.” We see, in our mind’s eye, not an amorphous soul, but a small, fragile bird chirping in anticipation of attracting a mate, a bird so fragile it would be easy prey for my cat. Emily’s hope is one pounce away from extinction. Nonetheless, her poem moves to gratitude that hope comforts without expecting anything from her. True, it has none of the planning and preparation of expectation, but hope is not fragile. It holds us in our own sturdy hands above the grave.

When does Dickinson hear the hopeful bird song? She hears it in the gale or on the chillest land or the strangest sea. We are most aware of hope when our lives face challenge. It faces off against another strong emotion, despair. Hope was the flag that preceded the march of youth from Marjory Douglas Stoneman High School to the steps of their nation’s capital. Students did not march to scream their despair, like King Lear howling to the heavens. They marched to speak their young hope for a violence-free nation, and it is that hope that sings in the gale. Hope looks forward, not backward.  Barack Obama based his drive to the presidency not on a slogan to “Make America Great Again”, but on hope. The Barack Obama “Hope” poster is an image of President Barak Obama. The image, designed by artist Shepard Fairey, was widely described as iconic.

Barack Obama based his drive to the presidency not on a slogan to “Make America Great Again”, but on hope. The Barack Obama “Hope” poster is an image of President Barak Obama. The image, designed by artist Shepard Fairey, was widely described as iconic.

It is President Obama’s version of hopethat connects with me in my seventy-fifth year. Words shift meanings when you enter the last couple decades of your life. My hopes are no longer so personal, though I may hope I don’t die of some long-drawn-out disease. I do know I will die, a knowledge I could shove aside in those years when my mirror didn’t offer me wrinkled skin and thinning hair. My hopes now are less personal and more universal. Having 75 years to look backwards, I have the courage to imagine 75 years forward in my absence. At a recent Seattle Arts and Lectures event, the host asked guest author Barbara Kingsolver where she found hope in today’s divided world. She replied that hope is a kind of energy she chooses to renew each day. To abandon hope, she would be abandoning her children, her grandchildren and the children of the world. Each day, as readily as pulling on her socks, she renews the energy of hope. I too renew hope in the storm for my grandchildren, for my planet. I may no longer imagine the June salad on my own dinner plate, but I can hope for food on the tables of a world where climate change has been acknowledged and ameliorated, where peoples around the world share the bounty of what each contributes.

April is almost here. I drive through the Suquamish Reservation to Hood Canal. The highway dips between stands of evergreens spaced by deciduous trees now wearing a yellow green hue, those fist buds on spare limbs, limbs that last week were winter stripped. The windshield wipers click rhythmically to clear steady rain. Like a chant, I hear the punctuated consonance of hope, hope, hope.

Archibald MacLeish writes in Ars Poetica, “For all the history of grief / An empty doorway and a maple leaf.” What profound absence he expresses in one metaphorical image, so that my heart hollows out with sadness as I picture that open doorway beyond which there is absence. In defining grief, a dictionary would settle for “deep, sadness, often lasting a long time.” The dictionary is accurate enough but cannot replicate the feeling of grief defined in MacLeish’s open door or the falling maple leaf.

Archibald MacLeish writes in Ars Poetica, “For all the history of grief / An empty doorway and a maple leaf.” What profound absence he expresses in one metaphorical image, so that my heart hollows out with sadness as I picture that open doorway beyond which there is absence. In defining grief, a dictionary would settle for “deep, sadness, often lasting a long time.” The dictionary is accurate enough but cannot replicate the feeling of grief defined in MacLeish’s open door or the falling maple leaf. Many Americans have left religion altogether because the Bible remains the cornerstone of churches, and in an empirical age, people will not subscribe to a belief in miracles such as virginal birth. Others, in some fundamentalist churches, turn off the reality button, permitting their literalism to deny what science disproves. The Bible itself abounds in contradictions, making “the word of God” as evasive as mercury spilled from a broken thermometer. For me, literal readings can make the Bible as shallow as a puddle in which we look no deeper than the reflection of our own face. Metaphorical readings expand in lakes and oceans, often feeding channels between islands no one mapped.

Many Americans have left religion altogether because the Bible remains the cornerstone of churches, and in an empirical age, people will not subscribe to a belief in miracles such as virginal birth. Others, in some fundamentalist churches, turn off the reality button, permitting their literalism to deny what science disproves. The Bible itself abounds in contradictions, making “the word of God” as evasive as mercury spilled from a broken thermometer. For me, literal readings can make the Bible as shallow as a puddle in which we look no deeper than the reflection of our own face. Metaphorical readings expand in lakes and oceans, often feeding channels between islands no one mapped.  Christ does not have to resurrect in the flesh, offering his wounds to Thomas or anyone else in doubt. Christ can “come again,” among his followers who, despairing his death, realize his teachings never left them, but will endure. Christ had risen!

Christ does not have to resurrect in the flesh, offering his wounds to Thomas or anyone else in doubt. Christ can “come again,” among his followers who, despairing his death, realize his teachings never left them, but will endure. Christ had risen! These are facts about Ms. Obama’s life there, but it was her metaphorical descriptions of her life from the South Side of Chicago to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue that helped me to feel what she felt. Metaphor opens the envelope for empathy. What a wonderful organ our brain is that we can look at the moon while Alfred Noyes describes “the moon is a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas,” and we can see a full sail sailing ship in rough seas and at the same time a real moon, flitting in a tumultuous dance among clouds.

These are facts about Ms. Obama’s life there, but it was her metaphorical descriptions of her life from the South Side of Chicago to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue that helped me to feel what she felt. Metaphor opens the envelope for empathy. What a wonderful organ our brain is that we can look at the moon while Alfred Noyes describes “the moon is a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas,” and we can see a full sail sailing ship in rough seas and at the same time a real moon, flitting in a tumultuous dance among clouds.

In “retirement,” I became the nanny as well as Nana, to my grandchildren, reading them books, instructing them on names of mushrooms on our walks to the park, and later pressing their chubby palms in to dough as we kneaded loaves of bread.

In “retirement,” I became the nanny as well as Nana, to my grandchildren, reading them books, instructing them on names of mushrooms on our walks to the park, and later pressing their chubby palms in to dough as we kneaded loaves of bread. Fantasies serve to get us away without getting away. Once retirement comes, we have finally escaped those parts of our jobs we didn’t enjoy. Yet clinging to those displeasures like a demanding child, are those tasks that actually fulfilled us. In teaching, fulfillment might be that very clinging child whose progress depended on our support. From serving others, our work and ourselves gain importance. I confess that upon leaving Woodinville High School, I couldn’t imagine how seniors unable to take my college prep English class would ever survive in college. (Time here for laughter)

Fantasies serve to get us away without getting away. Once retirement comes, we have finally escaped those parts of our jobs we didn’t enjoy. Yet clinging to those displeasures like a demanding child, are those tasks that actually fulfilled us. In teaching, fulfillment might be that very clinging child whose progress depended on our support. From serving others, our work and ourselves gain importance. I confess that upon leaving Woodinville High School, I couldn’t imagine how seniors unable to take my college prep English class would ever survive in college. (Time here for laughter) I walked to and from the University of Washington my final years teaching on campus. I walked down the hill each morning, stopping for a latte and scone on the way. At the coffee shop, Jackson, a garrulous Scottish baker, swapped stories with me as I bit into one of her jam-filled scones she pronounced as “Skhanz.” On the way home, I took the opposite bridge across Lake Washington’s ship canal and back up Capitol Hill. Seasons blessed my exercise with meditation on falling chestnuts and blooming early plums. In retirement, I missed that walk, though I could still walk down and around the university whenever I wished. But without a purpose? Years passed until I began offering to walk my daughter’s golden retriever down the hill and through campus, where the dog’s “I love people” expressions and wagging tail attract undergrads who miss their dogs left at home. Now the walk resumes with “purpose. ”

I walked to and from the University of Washington my final years teaching on campus. I walked down the hill each morning, stopping for a latte and scone on the way. At the coffee shop, Jackson, a garrulous Scottish baker, swapped stories with me as I bit into one of her jam-filled scones she pronounced as “Skhanz.” On the way home, I took the opposite bridge across Lake Washington’s ship canal and back up Capitol Hill. Seasons blessed my exercise with meditation on falling chestnuts and blooming early plums. In retirement, I missed that walk, though I could still walk down and around the university whenever I wished. But without a purpose? Years passed until I began offering to walk my daughter’s golden retriever down the hill and through campus, where the dog’s “I love people” expressions and wagging tail attract undergrads who miss their dogs left at home. Now the walk resumes with “purpose. ” I email the monthly poem to those not close-by to take a poem from the box. On telling those folks this is my 15th year with the poetry box, my husband’s niece wrote, “We appreciate the lessons and places you’ve taken us with your 15-year commitment to the Poetry Box. Roger and I would likely never discuss poetry without the Poetry Box so thank you for this gift!”

I email the monthly poem to those not close-by to take a poem from the box. On telling those folks this is my 15th year with the poetry box, my husband’s niece wrote, “We appreciate the lessons and places you’ve taken us with your 15-year commitment to the Poetry Box. Roger and I would likely never discuss poetry without the Poetry Box so thank you for this gift!”

Today, some may be frosting cookies to set on a plate by the fireplace for when Santa descends. The custom may continue each year, long after the children have left for college. Many families either follow established traditions or stumble on to their own, without realizing a little habit or ritual grows like a child whose appetite wants feeding.

Today, some may be frosting cookies to set on a plate by the fireplace for when Santa descends. The custom may continue each year, long after the children have left for college. Many families either follow established traditions or stumble on to their own, without realizing a little habit or ritual grows like a child whose appetite wants feeding. Influenced by the etchings of Rembrandt, Allan drew an elysian image of a descending angel, etched it in a metal plate, and ran twenty-five original prints for those to whom we wanted to send our Christmas greeting. We made no commitment to ourselves or to others that there would be another the following year.

Influenced by the etchings of Rembrandt, Allan drew an elysian image of a descending angel, etched it in a metal plate, and ran twenty-five original prints for those to whom we wanted to send our Christmas greeting. We made no commitment to ourselves or to others that there would be another the following year. Inevitably, we needed to trust the reproducing work to a professional with a large studio. Allan still creates the image and cuts the stencils before passing on the stencils to Tori, our third professional printmaker.

Inevitably, we needed to trust the reproducing work to a professional with a large studio. Allan still creates the image and cuts the stencils before passing on the stencils to Tori, our third professional printmaker. Then there is the Washington Athletic Club group. What started as a small gathering of early-morning athletes celebrating a Holiday Season breakfast, grew to sixty strong. Gordy dresses as Santa. After handing out our cards, Allan describes the artistic process, and acknowledges the fellowship of starting each day with a workout among friends. I read the poem aloud. Each year, we wonder if maybe we should forego the task of contacting catering, renting a room, taking sign-ups in the locker rooms. But each year, club members ask, “What is the date of this year’s breakfast? We love that tradition.” Suspending a “Tradition” can feel like desertion.

Then there is the Washington Athletic Club group. What started as a small gathering of early-morning athletes celebrating a Holiday Season breakfast, grew to sixty strong. Gordy dresses as Santa. After handing out our cards, Allan describes the artistic process, and acknowledges the fellowship of starting each day with a workout among friends. I read the poem aloud. Each year, we wonder if maybe we should forego the task of contacting catering, renting a room, taking sign-ups in the locker rooms. But each year, club members ask, “What is the date of this year’s breakfast? We love that tradition.” Suspending a “Tradition” can feel like desertion.

I jumped to Obama’s defense. “Are you aware?” I asked my friend, “that you regularly disparage people who have money, although you are quite wealthy by any standards?” My words reduced her to tears. I felt as if I had wounded my sister.

I jumped to Obama’s defense. “Are you aware?” I asked my friend, “that you regularly disparage people who have money, although you are quite wealthy by any standards?” My words reduced her to tears. I felt as if I had wounded my sister.

Do Americans more freely offer opinions than people from other countries? If so, perhaps there is a link to the way we teach our students. When teaching high school English, I may have started the class with “What happened” questions just to review the plot of our current book, but I soon moved on to the Why questions, those asking for opinions, granted opinions backed up by the text. We call it critical thinking, and American schools pride themselves in educating not only willful students but also ones who think critically.

Do Americans more freely offer opinions than people from other countries? If so, perhaps there is a link to the way we teach our students. When teaching high school English, I may have started the class with “What happened” questions just to review the plot of our current book, but I soon moved on to the Why questions, those asking for opinions, granted opinions backed up by the text. We call it critical thinking, and American schools pride themselves in educating not only willful students but also ones who think critically. So many balls in the air at one time. Then back to Fox News, or CNN, or any other show touting itself as a news source. Good luck at finding anything approaching factual news. A body lies on the pavement, a VW in the ditch, but the commentator is rushing around with a microphone asking twenty people what they THINK happened.

So many balls in the air at one time. Then back to Fox News, or CNN, or any other show touting itself as a news source. Good luck at finding anything approaching factual news. A body lies on the pavement, a VW in the ditch, but the commentator is rushing around with a microphone asking twenty people what they THINK happened.

Later in the morning I meet with a woman I have known for twenty-five years. She asks to meet with me to discuss a sadness in her life for which she believes I might have a shared experience. We have family and friends in common, and they are the subject of her grief. First, we catch up on little things we do to fill our days. Then, testing a shared comfort, she begins to tell her personal story of a loss she experienced years before we met. She pauses. Because I know the Girl Talk script, I sense she is waiting for me to tell of my own loss years before we met. From our stories, there might not arise exact similarities, but there will be a kind of universality of experience that brings understanding to a sad occurrence. People seek reasons for their pain, but will settle for parallels, if reasons can’t be found.

Later in the morning I meet with a woman I have known for twenty-five years. She asks to meet with me to discuss a sadness in her life for which she believes I might have a shared experience. We have family and friends in common, and they are the subject of her grief. First, we catch up on little things we do to fill our days. Then, testing a shared comfort, she begins to tell her personal story of a loss she experienced years before we met. She pauses. Because I know the Girl Talk script, I sense she is waiting for me to tell of my own loss years before we met. From our stories, there might not arise exact similarities, but there will be a kind of universality of experience that brings understanding to a sad occurrence. People seek reasons for their pain, but will settle for parallels, if reasons can’t be found. Gossiping is inherently judgmental, and I regret that it is more often associated with women. But men gossip too. They tell about a business rival who cheats on his income tax. Men’s Sports Gossip (sometimes referred to as “Locker Room Talk”) can be as rough as the sports they discuss.

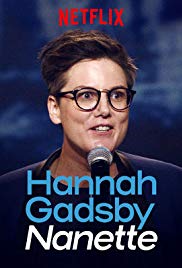

Gossiping is inherently judgmental, and I regret that it is more often associated with women. But men gossip too. They tell about a business rival who cheats on his income tax. Men’s Sports Gossip (sometimes referred to as “Locker Room Talk”) can be as rough as the sports they discuss. The stand-up comedian, Hannah Gadsby from Tasmania, based her humor on the awkward lives of lesbian women. A lesbian herself, she told about her own experiences suffering criticism and misunderstanding. As the show continued, what was at first humorous, became tragic. Annoyance grew to righteous indignation. What she said was no longer funny. The show was, however, profound. My husband didn’t enjoy the show, because of Hannah’s expressed anger, even though he sympathized with her many grievances. If she had spoken softly and slowly, her voice not pitched in indignation, I wonder if he would have more readily accepted the truths she offered.

The stand-up comedian, Hannah Gadsby from Tasmania, based her humor on the awkward lives of lesbian women. A lesbian herself, she told about her own experiences suffering criticism and misunderstanding. As the show continued, what was at first humorous, became tragic. Annoyance grew to righteous indignation. What she said was no longer funny. The show was, however, profound. My husband didn’t enjoy the show, because of Hannah’s expressed anger, even though he sympathized with her many grievances. If she had spoken softly and slowly, her voice not pitched in indignation, I wonder if he would have more readily accepted the truths she offered.

. And there you are — all stories are love stories, because through them we bond as we walk along the tangled paths of our human condition.

. And there you are — all stories are love stories, because through them we bond as we walk along the tangled paths of our human condition.

How many Snicker Bars or Peanut Butter cups does one child need? Does any child remember what house gives out Milk Duds and which Nestles Crunch? Little distinction, even less distinction in flavor or freshness. Super markets shove bags of Halloween candy on their shelves in late August.

How many Snicker Bars or Peanut Butter cups does one child need? Does any child remember what house gives out Milk Duds and which Nestles Crunch? Little distinction, even less distinction in flavor or freshness. Super markets shove bags of Halloween candy on their shelves in late August. Below them we dumped the unfamiliar, and therefore suspect, sopping honey confection. My adult self longs to return to the front door to be given a second chance. From many houses we got apples, always apples, barely welcomed in our greed for sweets. Mom separated them out from our Trick or Treat bag, parsing them out for school lunches. She also saved the nickels given by those unprepared to bake. Once there was a quarter among the change.

Below them we dumped the unfamiliar, and therefore suspect, sopping honey confection. My adult self longs to return to the front door to be given a second chance. From many houses we got apples, always apples, barely welcomed in our greed for sweets. Mom separated them out from our Trick or Treat bag, parsing them out for school lunches. She also saved the nickels given by those unprepared to bake. Once there was a quarter among the change.

I borrowed my brother’s leather cowboy vest, redolent with his own sweat that I identified with horse flesh. His cap gun hung heavily from my non-existent hips. If I were lucky, he would share a red roll of caps, their explosive pops filling my lungs with sweet sulfur.

I borrowed my brother’s leather cowboy vest, redolent with his own sweat that I identified with horse flesh. His cap gun hung heavily from my non-existent hips. If I were lucky, he would share a red roll of caps, their explosive pops filling my lungs with sweet sulfur. It is only an occasional child, usually a young one, who has changed identity for the night, who growls like the furry beast it is. I long for role-playing, for the ferocious tiger who will dare me to open the door wider. I hold out the wide wooden bowl brimming with mini Snickers and Tootsie Pops. Each year the packages shrink, but the kids don’t seem to notice. Their plastic pumpkin carriers are brimming with replicas of what we are giving. Over their shoulders, the little monsters thank us as they race back down the stairs to the sidewalk where an adult or two waits to escort them to the next house. As they secure their children’s sticky hands, does their tongue remember the taste of their own childhood? Gone are the days when children ran out the front door as soon as dusk swallowed the maple trees, to tag along with older siblings, combing the darkening streets until the soiled pillow case, filled with treats, weighed them down. Then it was time to return home to parents, unconcerned about absence after dark, sitting by a lamp reading until their costumed children had played out their one-night characters and were ready for sweetened sleep.

It is only an occasional child, usually a young one, who has changed identity for the night, who growls like the furry beast it is. I long for role-playing, for the ferocious tiger who will dare me to open the door wider. I hold out the wide wooden bowl brimming with mini Snickers and Tootsie Pops. Each year the packages shrink, but the kids don’t seem to notice. Their plastic pumpkin carriers are brimming with replicas of what we are giving. Over their shoulders, the little monsters thank us as they race back down the stairs to the sidewalk where an adult or two waits to escort them to the next house. As they secure their children’s sticky hands, does their tongue remember the taste of their own childhood? Gone are the days when children ran out the front door as soon as dusk swallowed the maple trees, to tag along with older siblings, combing the darkening streets until the soiled pillow case, filled with treats, weighed them down. Then it was time to return home to parents, unconcerned about absence after dark, sitting by a lamp reading until their costumed children had played out their one-night characters and were ready for sweetened sleep.

I don’t think I have run more than 6 miles in 2-mile increments, since 2016, when I ran the half marathon (another last minute decision) . This Sunday, I turn on I-Tunes on my phone at the start of the 10K. It will take only two complete replays of Pink Martini’s “Get Happy” album to keep me company until the finish line.

I don’t think I have run more than 6 miles in 2-mile increments, since 2016, when I ran the half marathon (another last minute decision) . This Sunday, I turn on I-Tunes on my phone at the start of the 10K. It will take only two complete replays of Pink Martini’s “Get Happy” album to keep me company until the finish line. Its force reminds me that I am a slender woman who with a big gust could be blown off the road to topple on to the grassy fields. I pass ancient apple trees, their trunks bent in testament to the wind, fallen apples fragrant with fermentation.

Its force reminds me that I am a slender woman who with a big gust could be blown off the road to topple on to the grassy fields. I pass ancient apple trees, their trunks bent in testament to the wind, fallen apples fragrant with fermentation. I begin the slow ascent south that will take me by the field where Racer the horse used to run to greet me for a fistful of grass. Gone now, his spirit keeps me running. Soon I approach the water stand outside our own drift-wood fence where my husband sets out paper cups of orange and lime Gatorade on a small table. I grab, gulp and go on. I know the hill rises steeply for another eighth of a mile, the open view from the top, showing the bay is at high tide, the longer autumn shadows splitting the sun on the water’s surface. Blackberries thrive on that hill top, berries now dried and fragrant as old wine. Turn-around for the 10K comes in a dip in the road, darkened on both sides by Palmers’ woods, old as the peninsula itself in giant Doug Firs and Big Leaf Maple trees. If I were not mid-race, their deep woods would invite me in. But here is turn-around, monitored by Linda and Stan Herzog. Linda calls my name. Stan snaps a photo.

I begin the slow ascent south that will take me by the field where Racer the horse used to run to greet me for a fistful of grass. Gone now, his spirit keeps me running. Soon I approach the water stand outside our own drift-wood fence where my husband sets out paper cups of orange and lime Gatorade on a small table. I grab, gulp and go on. I know the hill rises steeply for another eighth of a mile, the open view from the top, showing the bay is at high tide, the longer autumn shadows splitting the sun on the water’s surface. Blackberries thrive on that hill top, berries now dried and fragrant as old wine. Turn-around for the 10K comes in a dip in the road, darkened on both sides by Palmers’ woods, old as the peninsula itself in giant Doug Firs and Big Leaf Maple trees. If I were not mid-race, their deep woods would invite me in. But here is turn-around, monitored by Linda and Stan Herzog. Linda calls my name. Stan snaps a photo. This is an oyster run, celebrating Quilcene’s famous oysters, so the aroma of wood coals and garlic bread already permeates the air. Depending on where you stand, it is fried food or local ale to keep a mind motivated for returning to this spot after the race. Everyone is happy. Those who know me, cheer me on. They seem more confident than I that I will make it the whole way. I will make new friends as the race begins, when I discover whose pace falls in with mine. That is how I meet Michele and Meg. We don’t talk much during the run. All of us are tuned in to whatever music lifts one foot in front of the other, but there are moments of encouragement among us. Good going. Feel free to pass. Yes, the hills are tough for me too. I pass a woman with her arm around her young son, a stalky boy who clearly has some cognitive impairment. He smiles widely at me.

This is an oyster run, celebrating Quilcene’s famous oysters, so the aroma of wood coals and garlic bread already permeates the air. Depending on where you stand, it is fried food or local ale to keep a mind motivated for returning to this spot after the race. Everyone is happy. Those who know me, cheer me on. They seem more confident than I that I will make it the whole way. I will make new friends as the race begins, when I discover whose pace falls in with mine. That is how I meet Michele and Meg. We don’t talk much during the run. All of us are tuned in to whatever music lifts one foot in front of the other, but there are moments of encouragement among us. Good going. Feel free to pass. Yes, the hills are tough for me too. I pass a woman with her arm around her young son, a stalky boy who clearly has some cognitive impairment. He smiles widely at me. And finally, the physical part. I want to remember when the endorphins kick in after the 2nd kilometer. I am running downhill by the green apple tree where yesterday I stole enough for a pie. I look up to Mt. Walker ahead and my chest fills with autumn-washed air. Breath is wonderful. Deep, deep breath is exhilarating. I could run forever on this feeling. I could spread my arms and mimic the gulls and ravens swooping over the bay. I start to write this essay in my head so no feeling will fail to remain.

And finally, the physical part. I want to remember when the endorphins kick in after the 2nd kilometer. I am running downhill by the green apple tree where yesterday I stole enough for a pie. I look up to Mt. Walker ahead and my chest fills with autumn-washed air. Breath is wonderful. Deep, deep breath is exhilarating. I could run forever on this feeling. I could spread my arms and mimic the gulls and ravens swooping over the bay. I start to write this essay in my head so no feeling will fail to remain.

Only after one takes my picture, do I realize my face is raspberry red. I sit by another runner on the grass while our bodies cool. The sun is full out, but I am beginning to chill. My newly acquainted runner drives me back to my cottage where I peel off my running pants and shirt. My tongue tastes salt. My skin feels like salt. I realize I have excreted a good amount of salt water. As soon as I persuade myself to leave the hot tub jets, I will drink a tall glass of water. Every part of my body has been used: my feet, my legs, even my shoulders and neck. I should feel beat up, but I don’t. I feel twenty years younger. Maybe I will get back into this running thing.

Only after one takes my picture, do I realize my face is raspberry red. I sit by another runner on the grass while our bodies cool. The sun is full out, but I am beginning to chill. My newly acquainted runner drives me back to my cottage where I peel off my running pants and shirt. My tongue tastes salt. My skin feels like salt. I realize I have excreted a good amount of salt water. As soon as I persuade myself to leave the hot tub jets, I will drink a tall glass of water. Every part of my body has been used: my feet, my legs, even my shoulders and neck. I should feel beat up, but I don’t. I feel twenty years younger. Maybe I will get back into this running thing.