Certain phrases stick with me like burrs to my clothing when walking through a grassy field. No sense in trying to brush them off; besides, to do so I may discard something of value, that in the right surroundings could save my life. This week’s sticky burr of a quotation comes from John Philip Newell’s Sacred Earth Sacred Soul, in which he covers a chronology of Celtic Christianity with short biographies of theologians as far back as the 4th century who lived a Celtic spirituality.

Perhaps the phrase stuck for its alliteration – easy to hear those “p’s” skipping from my lips as I juxtapose pines and politicians. Nonetheless, White’s phrase stays with me. I want to consider my relationship to Nature and Politicians. How do I start my days? I often turn on NPR for the morning news and commentary that is 99% depressing. I hear voices of politicians in their most recent declarations of intention. Their words are consistent with whatever feeds their ambition. There is no plot to follow. I could skip listening to Morning Edition for a year, then return to it a year later to discover I had not missed a thing in the tenor of our time. Rather like a bad soap opera. For variety, I could switch to another newsfeed, perhaps not aligned to my feelings about the state of the world, not to mention the condition of our country. But would any of these broadcasts enhance my life? Would their negativity call me to action? Would I come to a fuller understanding of my purpose on the planet? Ironically, I am often listening to Morning Edition on my walks at dawn from my house down to and around the U of W campus, a six-mile morning walk under old established trees in old established neighborhoods: blossoming cherry trees in April, vermillion maples in autumn, tall proud pines and cedars all year long.

Now here comes Scottish poet, Kenneth White suggesting I might join him in listening to the trees rather than the politicians. How do I listen to the trees? The cherry blossoms are speaking beauty and rebirth. The autumnal maples and sweet gums recite their own poetry. Poet Gerard Manly Hopkins evokes images of trees in fall and mourns the imminent death of summer “Margaret are you grieving “ over Goldengrove unleaving? … worlds of wanwood leafmeal lie.” Then winter arrives and Robert Frost reminds us “The woods are lovely, dark and deep.” Surely the poets help me listen to the trees. Yet even without the writers, if I block out cars and pedestrians passing by, and if I concentrate, I hear the trees. Their leaves whisper in summer breezes. Occasionally, such as this very dry summer, the trees crack and snap, discarding a branch that lands on the sidewalk. These are city images. Now if I take myself to the woods, I remember recent books I read about trees, teaching that there is a conversation between alders and the firs, one fast growing and nutritious to the welfare of the other. Is that alder speaking to the fir? I guess it depends on how we define language.

And if we can listen to the trees, especially hearing their needs for water and space and clean air, can the trees hear us? Although we don’t share the same language, we are all living things. Life communicates. When my husband and I began to restore a clear-cut lot we purchased after the owners sold the trees and evacuated their property, we decided on a variety of trees, some 20 -foot Douglas Firs purchased from neighbors across the road, and some small fruit trees for a space left vacant when the previous owners disposed of their cabin. One pear tree initially grew fast and tall, but its pears did not thrive. Insect-infested and hard, the few pears on gnarled branches fell to the ground where deer consumed them before we had a chance. Every time my husband and I walked by the pear tree, he said, “That tree looks bad. It really has to go.” So how would you feel if every time someone passed you, these were the descriptive words for you? You would want to die, right? And of course, the pear tree died. Not wanting to accuse my husband of projecting a death wish on the tree, I nonetheless registered the lesson. Years later, I desired a Katsura tree, for there are several in Seattle where I walk. In autumn the pink leaves wave a fragrance I associate with the sweet smell of cotton candy. From the moment we planted it, I have welcomed that Katsura tree almost every day. I tell it how lovely and thriving it is, even though a workman backed his tractor into the trunk last year, leaving a two-foot scrape on the trunk. “Good morning, Katsura. I am so glad you are here. Looking forward to your autumnal fragrance.” It is now almost twenty-five feet, its leaves fluttering in the dappled sunlight, even though nearby cedars consume a great deal of available light.

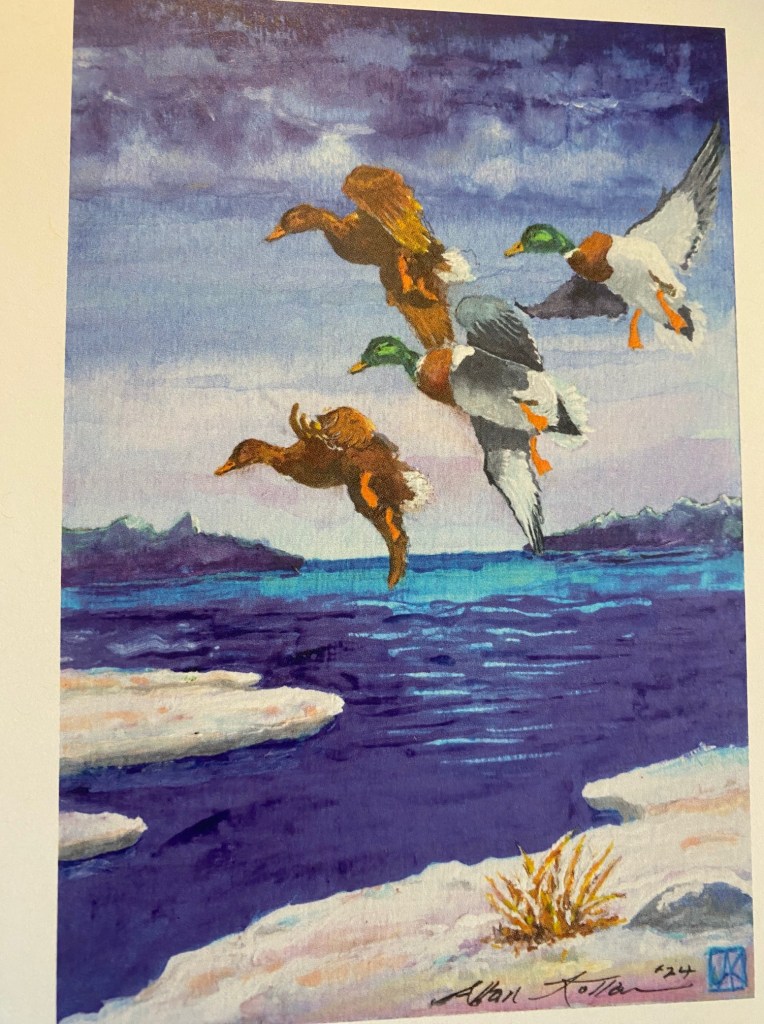

On the way back to Seattle Monday morning, three gigantic logging trucks rolled on to the ferry ahead of us. Their beds were piled with logs about five feet in diameter and perhaps fifty feet or more in length. These were not the usual harvest of tree farms. Rather they looked like the established trees from the National Olympic Forest. I recall Donald Trump’s call for opening-up national forests to loggers. I can imagine what birds and animals would say in response. But what about the trees? Is any politician listening to the pines?