Holiday parties bring together long-time friends who don’t keep in touch on a regular basis, so conversations often begin with inquiries about what engages us these days. Telling my friend Lynn that I had started a blog featuring thoughts as a septuagenarian, she suggested I write one on retirement. Lynn complains that her husband, who recently “retired” after 40 plus years teaching high school art and coaching soccer, has retired his regular paycheck but not his person. Soon after packing up his classroom, he volunteered to show up for any little jobs around school. He can fix anything, no payment required. There he returns many a weekday morning, in his green VW bug, its odometer brimming with commuter miles.

I sympathize with both Lynn and her husband. When I retired from teaching high school over twenty years ago, my identity felt as unstable as a leaf clinging to an autumnal oak. My daughter consoled me with her version of an old saying: “You can take my mom out of the classroom, but you can’t take the classroom out of my mom.” I would continue to behave and to think of myself as a teacher.  In “retirement,” I became the nanny as well as Nana, to my grandchildren, reading them books, instructing them on names of mushrooms on our walks to the park, and later pressing their chubby palms in to dough as we kneaded loaves of bread.

In “retirement,” I became the nanny as well as Nana, to my grandchildren, reading them books, instructing them on names of mushrooms on our walks to the park, and later pressing their chubby palms in to dough as we kneaded loaves of bread.

While working in the pay-day world, we fantasize about retirement, especially when our backbones ache for sitting through late-day faculty meetings, or our Sunday afternoons disappear under stacks of essays in need of grading. I had two fantasies: one was to wait tables so I could still enjoy the company of others, even serve them a pleasant dining experience, but not wake up in the middle of the night revising a lesson plan to better suit a challenged student. The other fantasy was to drive a big truck, sitting high behind the wheel watching the landscapes exchange their variable beauty from one state to another. There would be no student hovering by my side to complain about a grade — the cacophony of high school pep assemblies replaced by soft jazz from the truck radio. This fantasy focused me so completely that one morning I almost missed my freeway exit to school when I saw the sign: North to Vancouver, B.C.

No doubt, restaurant servers and truck drivers would educate me on these naïve perceptions of their jobs. My husband reminds me that driving the truck is only part of the job. I would have to be strong enough to unload it upon arrival.  Fantasies serve to get us away without getting away. Once retirement comes, we have finally escaped those parts of our jobs we didn’t enjoy. Yet clinging to those displeasures like a demanding child, are those tasks that actually fulfilled us. In teaching, fulfillment might be that very clinging child whose progress depended on our support. From serving others, our work and ourselves gain importance. I confess that upon leaving Woodinville High School, I couldn’t imagine how seniors unable to take my college prep English class would ever survive in college. (Time here for laughter)

Fantasies serve to get us away without getting away. Once retirement comes, we have finally escaped those parts of our jobs we didn’t enjoy. Yet clinging to those displeasures like a demanding child, are those tasks that actually fulfilled us. In teaching, fulfillment might be that very clinging child whose progress depended on our support. From serving others, our work and ourselves gain importance. I confess that upon leaving Woodinville High School, I couldn’t imagine how seniors unable to take my college prep English class would ever survive in college. (Time here for laughter)

Retirees miss not only their jobs but the routine that employment offers. Sure, my friend’s husband is still driving back to his old school.  I walked to and from the University of Washington my final years teaching on campus. I walked down the hill each morning, stopping for a latte and scone on the way. At the coffee shop, Jackson, a garrulous Scottish baker, swapped stories with me as I bit into one of her jam-filled scones she pronounced as “Skhanz.” On the way home, I took the opposite bridge across Lake Washington’s ship canal and back up Capitol Hill. Seasons blessed my exercise with meditation on falling chestnuts and blooming early plums. In retirement, I missed that walk, though I could still walk down and around the university whenever I wished. But without a purpose? Years passed until I began offering to walk my daughter’s golden retriever down the hill and through campus, where the dog’s “I love people” expressions and wagging tail attract undergrads who miss their dogs left at home. Now the walk resumes with “purpose. ”

I walked to and from the University of Washington my final years teaching on campus. I walked down the hill each morning, stopping for a latte and scone on the way. At the coffee shop, Jackson, a garrulous Scottish baker, swapped stories with me as I bit into one of her jam-filled scones she pronounced as “Skhanz.” On the way home, I took the opposite bridge across Lake Washington’s ship canal and back up Capitol Hill. Seasons blessed my exercise with meditation on falling chestnuts and blooming early plums. In retirement, I missed that walk, though I could still walk down and around the university whenever I wished. But without a purpose? Years passed until I began offering to walk my daughter’s golden retriever down the hill and through campus, where the dog’s “I love people” expressions and wagging tail attract undergrads who miss their dogs left at home. Now the walk resumes with “purpose. ”

Routines plug us into the circadian rhythms of a day. My husband’s friend who this year accepted “forced” retirement for those over 70, is depressed. “I don’t know where to go mornings,” he said, with the grief of loss. Something needs to call us, and now it is time to listen for new voices. With time, they may speak from within.

Each Labor Day I feel called to buy notebooks and new shoes. I have not returned to a classroom of my own; however, I have volunteered for after-school homework help at the library and a couple of years tutoring in a ninth-grade classroom at Garfield High. In 2004, a poetry box I affixed to the fence surrounding our home offers a routine of selecting and printing a poem I copy each month.  I email the monthly poem to those not close-by to take a poem from the box. On telling those folks this is my 15th year with the poetry box, my husband’s niece wrote, “We appreciate the lessons and places you’ve taken us with your 15-year commitment to the Poetry Box. Roger and I would likely never discuss poetry without the Poetry Box so thank you for this gift!”

I email the monthly poem to those not close-by to take a poem from the box. On telling those folks this is my 15th year with the poetry box, my husband’s niece wrote, “We appreciate the lessons and places you’ve taken us with your 15-year commitment to the Poetry Box. Roger and I would likely never discuss poetry without the Poetry Box so thank you for this gift!”

The recent government shutdown leaves many feeling helpless. Many complain, “But what can I do?” That sentiment is akin to the helplessness experienced with retirement. Our years after the routine of salaried employment may offer time to put usefulness in perspective. For me, often a poem rises from memory. John Milton, who felt his career as a writer was his service to God, lamented how his blindness curtailed his writing. From his sorrow came Sonnet 19, that concludes:

“God doth not need

Either man’s work or his own gifts; who best

Bear his mild yoke, they serve him best. His state

Is Kingly. Thousands at his bidding speed

And post o’er Land and Ocean without rest:

They also serve who only stand and wait.”

Today, some may be frosting cookies to set on a plate by the fireplace for when Santa descends. The custom may continue each year, long after the children have left for college. Many families either follow established traditions or stumble on to their own, without realizing a little habit or ritual grows like a child whose appetite wants feeding.

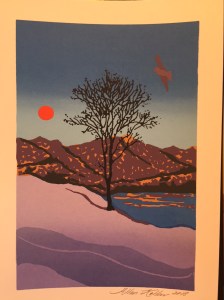

Today, some may be frosting cookies to set on a plate by the fireplace for when Santa descends. The custom may continue each year, long after the children have left for college. Many families either follow established traditions or stumble on to their own, without realizing a little habit or ritual grows like a child whose appetite wants feeding. Influenced by the etchings of Rembrandt, Allan drew an elysian image of a descending angel, etched it in a metal plate, and ran twenty-five original prints for those to whom we wanted to send our Christmas greeting. We made no commitment to ourselves or to others that there would be another the following year.

Influenced by the etchings of Rembrandt, Allan drew an elysian image of a descending angel, etched it in a metal plate, and ran twenty-five original prints for those to whom we wanted to send our Christmas greeting. We made no commitment to ourselves or to others that there would be another the following year. Inevitably, we needed to trust the reproducing work to a professional with a large studio. Allan still creates the image and cuts the stencils before passing on the stencils to Tori, our third professional printmaker.

Inevitably, we needed to trust the reproducing work to a professional with a large studio. Allan still creates the image and cuts the stencils before passing on the stencils to Tori, our third professional printmaker. Then there is the Washington Athletic Club group. What started as a small gathering of early-morning athletes celebrating a Holiday Season breakfast, grew to sixty strong. Gordy dresses as Santa. After handing out our cards, Allan describes the artistic process, and acknowledges the fellowship of starting each day with a workout among friends. I read the poem aloud. Each year, we wonder if maybe we should forego the task of contacting catering, renting a room, taking sign-ups in the locker rooms. But each year, club members ask, “What is the date of this year’s breakfast? We love that tradition.” Suspending a “Tradition” can feel like desertion.

Then there is the Washington Athletic Club group. What started as a small gathering of early-morning athletes celebrating a Holiday Season breakfast, grew to sixty strong. Gordy dresses as Santa. After handing out our cards, Allan describes the artistic process, and acknowledges the fellowship of starting each day with a workout among friends. I read the poem aloud. Each year, we wonder if maybe we should forego the task of contacting catering, renting a room, taking sign-ups in the locker rooms. But each year, club members ask, “What is the date of this year’s breakfast? We love that tradition.” Suspending a “Tradition” can feel like desertion.

A flowering vine blooms along East Quilcene Road. Its lavender blossoms are bubbles, like sweet peas, so I have called them wild sweet peas, until my neighbor recently shocked me, identifying the vine as vetch. Walking up the road Sunday afternoon, I saw a long, flowering vetch vine winding itself like a garland around a young pine tree. The vine used the tree as a support for its growth, an attractive decoration.

A flowering vine blooms along East Quilcene Road. Its lavender blossoms are bubbles, like sweet peas, so I have called them wild sweet peas, until my neighbor recently shocked me, identifying the vine as vetch. Walking up the road Sunday afternoon, I saw a long, flowering vetch vine winding itself like a garland around a young pine tree. The vine used the tree as a support for its growth, an attractive decoration.

Greta and I had our own cozy VRBO apartment and had just settled in for our first night to adjust to jet lag, when I realized my necklace was no longer around my neck. We both scoured the apartment to no avail. I did not want to dampen the holiday by laying my grief on my granddaughter. I made light of it all until she had fallen asleep. Then I texted my husband back in Seattle, wailing in cyberspace about the loss, how I had loved that necklace he had given me for an anniversary gift. I may even have asked his forgiveness for being so careless in fixing the clasp. His response? “Is that all, Mary? Look now, you still have Greta.” There he was again, my support in an unimagined way.

Greta and I had our own cozy VRBO apartment and had just settled in for our first night to adjust to jet lag, when I realized my necklace was no longer around my neck. We both scoured the apartment to no avail. I did not want to dampen the holiday by laying my grief on my granddaughter. I made light of it all until she had fallen asleep. Then I texted my husband back in Seattle, wailing in cyberspace about the loss, how I had loved that necklace he had given me for an anniversary gift. I may even have asked his forgiveness for being so careless in fixing the clasp. His response? “Is that all, Mary? Look now, you still have Greta.” There he was again, my support in an unimagined way.