“But I don’t want to go among mad people,” Alice remarked.

“Oh, you can’t help that,” said the Cat: “we’re all mad here.

(Alice in Wonderland)

If Lewis Carroll were alive and residing in Seattle today, he would find the perfect atmosphere for writing Alice in Wonderland: anxiety circles around where we are going and how we will get there, wherever there is.

“My dear, here we must run as fast as we can, just to stay in place. And if you wish to go anywhere you must run twice as fast as that.” (Red Queen: Through the Looking Class.)

First, there is the upcoming Washington State Democratic primary on Tuesday, although our ballots arrived in the mail almost two weeks ago.  In a city that is as Blue as any city can be, this primary looms as an important destination. Voting early left people struggling to discern, among six contenders, which best fit the ideal liberal candidate to beat Donald Trump in November. Those who suspected on March 7th there might be fewer candidates from which to select, held their ballots close to the chest until the race fell to two: Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders. These voters are basking in the wisdom of their patience. The early voters feel the disappointment of wasting their vote, like eating dessert too soon, while still being passionate about the entree.

In a city that is as Blue as any city can be, this primary looms as an important destination. Voting early left people struggling to discern, among six contenders, which best fit the ideal liberal candidate to beat Donald Trump in November. Those who suspected on March 7th there might be fewer candidates from which to select, held their ballots close to the chest until the race fell to two: Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders. These voters are basking in the wisdom of their patience. The early voters feel the disappointment of wasting their vote, like eating dessert too soon, while still being passionate about the entree.

Then the Corona Virus. Seattle prides itself for so much: the home of Microsoft and Amazon, stunning national parks, an abundance of green landscapes resulting from weeks of rain. This past week, the Vice President described Seattle as the tip of the spear in the Corona Virus, for having more cases and, sadly, more deaths, than any other city in the country. Seattleites are used to dealing with affluence, rapid growth and tourists. They are not accustomed to germs.  The University of Washington has suspended live classes for the next few weeks, and called home all students from their studies abroad. So too have other schools, public and private, are closing for at least two weeks. From our cottage two hours west of my Seattle church, I attended first-time online church services this morning. Prayer is necessary now, but not in a common location where many church members are over sixty-years-old, the population vulnerable to the Corona Virus.

The University of Washington has suspended live classes for the next few weeks, and called home all students from their studies abroad. So too have other schools, public and private, are closing for at least two weeks. From our cottage two hours west of my Seattle church, I attended first-time online church services this morning. Prayer is necessary now, but not in a common location where many church members are over sixty-years-old, the population vulnerable to the Corona Virus.

Yesterday on NPR, the talk-show host interviewed a local mental health professional about the anxiety shrouding our Seattle citizens. What can we do to lessen that anxiety? “For one thing,” the therapist said, “ we can all stop listening so often to the media.” Yes, that is all well and good, but one is also advised to stay tuned for alerts and closures. Yep, straight out of Alice in Wonderland. But the therapist had a useful antidote to anxiety: calm, single-focused meditation. “ Take time to notice something slow-moving such as a fallen leaf drifting downstream.” With her advice in mind, I focused here on our wooded property by Quilcene bay. Join me in looking closely at moss:

Lying thick upon a fallen log

its green promise of alive

soft as the morning fog

that moistens, that invites

you to touch what is close

was always there inching along

while you were running through the woods.

Today’s close-up is moss

beside unfolding ferns,

a talisman to tuck

in your breast pocket

while the sun scorches

the fog away

opening up another day.

Sea turtles feed on the greenery on rocks along the shore, so succumbing to slamming against the boulders is like an encouraging push forward to feasting. Huge shells, some the size of a dinner table, ride just below the water’s surface. Whether the flippers help the turtle to navigate at this point is unclear. Rather they seem to give in to the waves’ force, all decision-making left to momentum. There must be a lesson for us there, something about trusting what carries us ahead.

Sea turtles feed on the greenery on rocks along the shore, so succumbing to slamming against the boulders is like an encouraging push forward to feasting. Huge shells, some the size of a dinner table, ride just below the water’s surface. Whether the flippers help the turtle to navigate at this point is unclear. Rather they seem to give in to the waves’ force, all decision-making left to momentum. There must be a lesson for us there, something about trusting what carries us ahead. Those are five sequential questions for which I have no definitive answer. So much for Oceanography 101. No mind. Poetic connections to the waves complement what science offers. The string of curling waves evokes images of peppermint ribbon candy. When the wave hits the rocky coastline, it splashes high and frothy as thrilling fireworks, then recedes leaving a damp memory on the stones.

Those are five sequential questions for which I have no definitive answer. So much for Oceanography 101. No mind. Poetic connections to the waves complement what science offers. The string of curling waves evokes images of peppermint ribbon candy. When the wave hits the rocky coastline, it splashes high and frothy as thrilling fireworks, then recedes leaving a damp memory on the stones. I take cautious steps forward, letting the wavelets tease me, toes-first. Step, sink a little, step again. As the waves surge to my knees I look out, guessing where the next large wave will rise. Will it break on top of me, sucking me helplessly under, grinding my face to the sand? Or do I wait until the breaking point and dive within its incoming belly, emerging only when the wave has receded for the next roller behind it. I dive. How successful I feel emerging up through the wave that took me, then I swim in a parallel line to the beach, far enough out to spot the fish, but close enough to see the shore where I want to return.

I take cautious steps forward, letting the wavelets tease me, toes-first. Step, sink a little, step again. As the waves surge to my knees I look out, guessing where the next large wave will rise. Will it break on top of me, sucking me helplessly under, grinding my face to the sand? Or do I wait until the breaking point and dive within its incoming belly, emerging only when the wave has receded for the next roller behind it. I dive. How successful I feel emerging up through the wave that took me, then I swim in a parallel line to the beach, far enough out to spot the fish, but close enough to see the shore where I want to return. On each visit, we note how the waves have chewed up more of the beach and/or the retaining wall that keeps the condos high and dry. The beach was once long enough for an invigorating walk at low tide toward a cave in the far rocks, a place I led my small grandchildren where we imagined pirates storing chests of gold doubloons, then hurried back before an incoming tide flooded the crevices in the rock. No tide is low enough to allow that walk today. Nearby, huge tractors work to restore a wall that had shored up the property of a wealthy landowner, his estate now several feet closer to sinking into the sea. Once long, the beach now is but a patch of sand. From half a world away and in eighty-degree heat, melting ice caps deliver messages in the rising seas.

On each visit, we note how the waves have chewed up more of the beach and/or the retaining wall that keeps the condos high and dry. The beach was once long enough for an invigorating walk at low tide toward a cave in the far rocks, a place I led my small grandchildren where we imagined pirates storing chests of gold doubloons, then hurried back before an incoming tide flooded the crevices in the rock. No tide is low enough to allow that walk today. Nearby, huge tractors work to restore a wall that had shored up the property of a wealthy landowner, his estate now several feet closer to sinking into the sea. Once long, the beach now is but a patch of sand. From half a world away and in eighty-degree heat, melting ice caps deliver messages in the rising seas.

How excited they are to fill me in on what I failed to teach the year they were in my class. Here I could groan in 3-D cynicism, not to mention disappointment. Instead, I share their joy that their minds are still engaged learning about their English language and literature.

How excited they are to fill me in on what I failed to teach the year they were in my class. Here I could groan in 3-D cynicism, not to mention disappointment. Instead, I share their joy that their minds are still engaged learning about their English language and literature. In the final act, Hamlet is about to have a duel with Laertes, a fight that he will likely lose. Hamlet’s friend, Horatio, tries to deter him from the match, because Laertes is by far the better and more practiced swordsman. Hamlet won’t be dissuaded, saying, There’s special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be now, ‘tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come. The readiness is all. ( Hamlet, V, ii, 230-233). Hamlet knows he will likely die, so when he dies is not his concern. What is important is his readiness to die. He is ready. How lucky for Act 5 and for preparing the audience to accept the inevitability.

In the final act, Hamlet is about to have a duel with Laertes, a fight that he will likely lose. Hamlet’s friend, Horatio, tries to deter him from the match, because Laertes is by far the better and more practiced swordsman. Hamlet won’t be dissuaded, saying, There’s special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be now, ‘tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come. The readiness is all. ( Hamlet, V, ii, 230-233). Hamlet knows he will likely die, so when he dies is not his concern. What is important is his readiness to die. He is ready. How lucky for Act 5 and for preparing the audience to accept the inevitability. On the opposite side, there is humility in readiness. These are the agreements we make with each other to step out of our comfort zone, to try something new. One-two-three- ready . . . set . . . go! and I am leaping off a small ledge to cold waters when my brother encourages me to swim downstream.

On the opposite side, there is humility in readiness. These are the agreements we make with each other to step out of our comfort zone, to try something new. One-two-three- ready . . . set . . . go! and I am leaping off a small ledge to cold waters when my brother encourages me to swim downstream. Reading about the German environment prior to Hitler’s rise – the accepted antisemitism, distrust of immigrants (Roma), excessive nationalism, putting The Fatherland first – it is clear that enough of the German populace was ready for Hitler. He was duly elected in a “democratic” republic.

Reading about the German environment prior to Hitler’s rise – the accepted antisemitism, distrust of immigrants (Roma), excessive nationalism, putting The Fatherland first – it is clear that enough of the German populace was ready for Hitler. He was duly elected in a “democratic” republic. I hear myself reciting from another sacred text: For everything there is a season, and a time for every matter under heaven: . .. God has made everything beautiful in its time. (Ecclesiastes 3, 1 & 11). Yes, a time to plant and a time to sow . . .. Every year I jump the gun when my readiness does not match Mother Nature’s.

I hear myself reciting from another sacred text: For everything there is a season, and a time for every matter under heaven: . .. God has made everything beautiful in its time. (Ecclesiastes 3, 1 & 11). Yes, a time to plant and a time to sow . . .. Every year I jump the gun when my readiness does not match Mother Nature’s.

When I look outside of my own experience to other women’s lives, I see similar patterns of fulfilling needs for others, mostly domestic needs, that make others’ lives comfortable. Does the fulfilling of those needs enrich the “needed” woman? Would she have chosen the tasks without societal expectation?

When I look outside of my own experience to other women’s lives, I see similar patterns of fulfilling needs for others, mostly domestic needs, that make others’ lives comfortable. Does the fulfilling of those needs enrich the “needed” woman? Would she have chosen the tasks without societal expectation? or she sat before the television watching Murder She Wrote with Angela Lansberry,

or she sat before the television watching Murder She Wrote with Angela Lansberry,

Top on the siren call would be perceived needs from my grandchildren and daughter. My granddaughter, a college senior, emails me a draft of her senior English thesis for editing. Her request leapfrogs to the top of my to-do list, real or imagined. I am flattered to be needed, especially to be needed for something that acknowledges I have a brain, not only a scrub brush.

Top on the siren call would be perceived needs from my grandchildren and daughter. My granddaughter, a college senior, emails me a draft of her senior English thesis for editing. Her request leapfrogs to the top of my to-do list, real or imagined. I am flattered to be needed, especially to be needed for something that acknowledges I have a brain, not only a scrub brush.

A late September afternoon, I am walking home through Volunteer Park, past the playground, quiet as expectation now that children are back to school. Swings, slides, and sculptures for climbing stand silent midst a leaf-spotted lawn that borders Seattle’s historic Lakeview Cemetery. A chain link fence separates a high swinging child and rows of manicured tombstones, many erected in homage to the settlers who first populated our city with Gold Rush, timber-eager adventurers. Pausing before a limp swing lit with early autumn light, I am back seventeen years, lifting my toddler grandson into the swing, then swooshing the boy and swing for a high cemetery view. When both of us are ready to proceed to the slide, my grandson tells me, “I know, Nana, how all those people died.”

A late September afternoon, I am walking home through Volunteer Park, past the playground, quiet as expectation now that children are back to school. Swings, slides, and sculptures for climbing stand silent midst a leaf-spotted lawn that borders Seattle’s historic Lakeview Cemetery. A chain link fence separates a high swinging child and rows of manicured tombstones, many erected in homage to the settlers who first populated our city with Gold Rush, timber-eager adventurers. Pausing before a limp swing lit with early autumn light, I am back seventeen years, lifting my toddler grandson into the swing, then swooshing the boy and swing for a high cemetery view. When both of us are ready to proceed to the slide, my grandson tells me, “I know, Nana, how all those people died.” Well into my grandson’s nineteenth year, I have retold that story to my grandson and the entire family, so it is a chapter in our book of family humor and nostalgia. However, this morning, the passive swing not only reminds me of the funny story. I actually feel his three-year-old self is forever in that swing. Were he to ask, “Nana, push me,” I would not be surprised.

Well into my grandson’s nineteenth year, I have retold that story to my grandson and the entire family, so it is a chapter in our book of family humor and nostalgia. However, this morning, the passive swing not only reminds me of the funny story. I actually feel his three-year-old self is forever in that swing. Were he to ask, “Nana, push me,” I would not be surprised. Don’t tell me animals live only in the present with no vital memories. When it is time for us to go to our cottage, and we take out the cooler from the basement, our cats disappear. They know the cooler means travel, equals kitty carriers, equals confinement. We must put them in their carrier before even thinking of fetching the cooler. Yet remembering and simultaneous existence are not the same.

Don’t tell me animals live only in the present with no vital memories. When it is time for us to go to our cottage, and we take out the cooler from the basement, our cats disappear. They know the cooler means travel, equals kitty carriers, equals confinement. We must put them in their carrier before even thinking of fetching the cooler. Yet remembering and simultaneous existence are not the same. It circles around itself like a whirlpool in a pond, gathering newly dropped leaves as it turns. We are brought back around as we proceed forward. Have you heard the declaration, “I don’t want to go there?” I have. The sentence suggests a benefit to burying the past. Understood, as a way to avoid adversity, but today I am thinking that having lived through so many experiences with so many people, I am in a position to live in two or more places at once, and thus able to be more empathic with others who may be experiencing something for the first time.

It circles around itself like a whirlpool in a pond, gathering newly dropped leaves as it turns. We are brought back around as we proceed forward. Have you heard the declaration, “I don’t want to go there?” I have. The sentence suggests a benefit to burying the past. Understood, as a way to avoid adversity, but today I am thinking that having lived through so many experiences with so many people, I am in a position to live in two or more places at once, and thus able to be more empathic with others who may be experiencing something for the first time.

No matter what tasks we are doing, we stop to run through the open gate and plunge in for a swim, push out in a kayak. or balance on a paddle board as soon as a chart in that book registers eight feet or more. Winters, the high tides can exceed 13 feet, and when married to high winds, the sea trespasses, often knocking out the gate with a floating log, white caps swamping our lawn.

No matter what tasks we are doing, we stop to run through the open gate and plunge in for a swim, push out in a kayak. or balance on a paddle board as soon as a chart in that book registers eight feet or more. Winters, the high tides can exceed 13 feet, and when married to high winds, the sea trespasses, often knocking out the gate with a floating log, white caps swamping our lawn.

“I love the low tide, as much as the high tide,” he said, reaching for the binoculars to spot heron tiptoeing between the streams and the violet green swallows checking out the boxes he has raised on poles along the shore.

“I love the low tide, as much as the high tide,” he said, reaching for the binoculars to spot heron tiptoeing between the streams and the violet green swallows checking out the boxes he has raised on poles along the shore.

Changing tides inspire humility, helping me to accept what gifts I didn’t know were coming. Just as high winter tides carry a battering ram of a tree trunk to wipe out our driftwood fence, so the water retreats, dumping our fence and stairs at the end of the bay. Neighbors help us retrieve what is ours, and in our scavenging, we find even better planks for restoration. Low tides uncover oysters and clams: a table-is-set ebbing of culinary fame. Even baby crabs scramble along the shore. In late August, salmon return along the streams that lace the flats. Salmon battle determinedly up those streams between lines of families fishing for a big one to take home for dinner. The tides give and take away, like the hand of a natural god.

Changing tides inspire humility, helping me to accept what gifts I didn’t know were coming. Just as high winter tides carry a battering ram of a tree trunk to wipe out our driftwood fence, so the water retreats, dumping our fence and stairs at the end of the bay. Neighbors help us retrieve what is ours, and in our scavenging, we find even better planks for restoration. Low tides uncover oysters and clams: a table-is-set ebbing of culinary fame. Even baby crabs scramble along the shore. In late August, salmon return along the streams that lace the flats. Salmon battle determinedly up those streams between lines of families fishing for a big one to take home for dinner. The tides give and take away, like the hand of a natural god. If it is a Low – Low, I may forget that there ever were welcoming waves in front of our cottage. If it is a high tide day, I know I am riding a surface on a paddle board, head-high enjoying the sunset sink behind Mt. Townsend. Most days are those Low Highs or High Lows, but nothing is stagnant. All life is movement. We know the moon will turn from crescent to full, and the bay that emptied all but bubbling craters where clams breathe, will within hours, cover meandering streams with salt and sea.

If it is a Low – Low, I may forget that there ever were welcoming waves in front of our cottage. If it is a high tide day, I know I am riding a surface on a paddle board, head-high enjoying the sunset sink behind Mt. Townsend. Most days are those Low Highs or High Lows, but nothing is stagnant. All life is movement. We know the moon will turn from crescent to full, and the bay that emptied all but bubbling craters where clams breathe, will within hours, cover meandering streams with salt and sea.

Barack Obama based his drive to the presidency not on a slogan to “Make America Great Again”, but on hope. The Barack Obama “Hope” poster is an image of President Barak Obama. The image, designed by artist Shepard Fairey, was widely described as iconic.

Barack Obama based his drive to the presidency not on a slogan to “Make America Great Again”, but on hope. The Barack Obama “Hope” poster is an image of President Barak Obama. The image, designed by artist Shepard Fairey, was widely described as iconic.

Archibald MacLeish writes in Ars Poetica, “For all the history of grief / An empty doorway and a maple leaf.” What profound absence he expresses in one metaphorical image, so that my heart hollows out with sadness as I picture that open doorway beyond which there is absence. In defining grief, a dictionary would settle for “deep, sadness, often lasting a long time.” The dictionary is accurate enough but cannot replicate the feeling of grief defined in MacLeish’s open door or the falling maple leaf.

Archibald MacLeish writes in Ars Poetica, “For all the history of grief / An empty doorway and a maple leaf.” What profound absence he expresses in one metaphorical image, so that my heart hollows out with sadness as I picture that open doorway beyond which there is absence. In defining grief, a dictionary would settle for “deep, sadness, often lasting a long time.” The dictionary is accurate enough but cannot replicate the feeling of grief defined in MacLeish’s open door or the falling maple leaf. Many Americans have left religion altogether because the Bible remains the cornerstone of churches, and in an empirical age, people will not subscribe to a belief in miracles such as virginal birth. Others, in some fundamentalist churches, turn off the reality button, permitting their literalism to deny what science disproves. The Bible itself abounds in contradictions, making “the word of God” as evasive as mercury spilled from a broken thermometer. For me, literal readings can make the Bible as shallow as a puddle in which we look no deeper than the reflection of our own face. Metaphorical readings expand in lakes and oceans, often feeding channels between islands no one mapped.

Many Americans have left religion altogether because the Bible remains the cornerstone of churches, and in an empirical age, people will not subscribe to a belief in miracles such as virginal birth. Others, in some fundamentalist churches, turn off the reality button, permitting their literalism to deny what science disproves. The Bible itself abounds in contradictions, making “the word of God” as evasive as mercury spilled from a broken thermometer. For me, literal readings can make the Bible as shallow as a puddle in which we look no deeper than the reflection of our own face. Metaphorical readings expand in lakes and oceans, often feeding channels between islands no one mapped.  Christ does not have to resurrect in the flesh, offering his wounds to Thomas or anyone else in doubt. Christ can “come again,” among his followers who, despairing his death, realize his teachings never left them, but will endure. Christ had risen!

Christ does not have to resurrect in the flesh, offering his wounds to Thomas or anyone else in doubt. Christ can “come again,” among his followers who, despairing his death, realize his teachings never left them, but will endure. Christ had risen! These are facts about Ms. Obama’s life there, but it was her metaphorical descriptions of her life from the South Side of Chicago to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue that helped me to feel what she felt. Metaphor opens the envelope for empathy. What a wonderful organ our brain is that we can look at the moon while Alfred Noyes describes “the moon is a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas,” and we can see a full sail sailing ship in rough seas and at the same time a real moon, flitting in a tumultuous dance among clouds.

These are facts about Ms. Obama’s life there, but it was her metaphorical descriptions of her life from the South Side of Chicago to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue that helped me to feel what she felt. Metaphor opens the envelope for empathy. What a wonderful organ our brain is that we can look at the moon while Alfred Noyes describes “the moon is a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas,” and we can see a full sail sailing ship in rough seas and at the same time a real moon, flitting in a tumultuous dance among clouds.

In “retirement,” I became the nanny as well as Nana, to my grandchildren, reading them books, instructing them on names of mushrooms on our walks to the park, and later pressing their chubby palms in to dough as we kneaded loaves of bread.

In “retirement,” I became the nanny as well as Nana, to my grandchildren, reading them books, instructing them on names of mushrooms on our walks to the park, and later pressing their chubby palms in to dough as we kneaded loaves of bread. Fantasies serve to get us away without getting away. Once retirement comes, we have finally escaped those parts of our jobs we didn’t enjoy. Yet clinging to those displeasures like a demanding child, are those tasks that actually fulfilled us. In teaching, fulfillment might be that very clinging child whose progress depended on our support. From serving others, our work and ourselves gain importance. I confess that upon leaving Woodinville High School, I couldn’t imagine how seniors unable to take my college prep English class would ever survive in college. (Time here for laughter)

Fantasies serve to get us away without getting away. Once retirement comes, we have finally escaped those parts of our jobs we didn’t enjoy. Yet clinging to those displeasures like a demanding child, are those tasks that actually fulfilled us. In teaching, fulfillment might be that very clinging child whose progress depended on our support. From serving others, our work and ourselves gain importance. I confess that upon leaving Woodinville High School, I couldn’t imagine how seniors unable to take my college prep English class would ever survive in college. (Time here for laughter) I walked to and from the University of Washington my final years teaching on campus. I walked down the hill each morning, stopping for a latte and scone on the way. At the coffee shop, Jackson, a garrulous Scottish baker, swapped stories with me as I bit into one of her jam-filled scones she pronounced as “Skhanz.” On the way home, I took the opposite bridge across Lake Washington’s ship canal and back up Capitol Hill. Seasons blessed my exercise with meditation on falling chestnuts and blooming early plums. In retirement, I missed that walk, though I could still walk down and around the university whenever I wished. But without a purpose? Years passed until I began offering to walk my daughter’s golden retriever down the hill and through campus, where the dog’s “I love people” expressions and wagging tail attract undergrads who miss their dogs left at home. Now the walk resumes with “purpose. ”

I walked to and from the University of Washington my final years teaching on campus. I walked down the hill each morning, stopping for a latte and scone on the way. At the coffee shop, Jackson, a garrulous Scottish baker, swapped stories with me as I bit into one of her jam-filled scones she pronounced as “Skhanz.” On the way home, I took the opposite bridge across Lake Washington’s ship canal and back up Capitol Hill. Seasons blessed my exercise with meditation on falling chestnuts and blooming early plums. In retirement, I missed that walk, though I could still walk down and around the university whenever I wished. But without a purpose? Years passed until I began offering to walk my daughter’s golden retriever down the hill and through campus, where the dog’s “I love people” expressions and wagging tail attract undergrads who miss their dogs left at home. Now the walk resumes with “purpose. ” I email the monthly poem to those not close-by to take a poem from the box. On telling those folks this is my 15th year with the poetry box, my husband’s niece wrote, “We appreciate the lessons and places you’ve taken us with your 15-year commitment to the Poetry Box. Roger and I would likely never discuss poetry without the Poetry Box so thank you for this gift!”

I email the monthly poem to those not close-by to take a poem from the box. On telling those folks this is my 15th year with the poetry box, my husband’s niece wrote, “We appreciate the lessons and places you’ve taken us with your 15-year commitment to the Poetry Box. Roger and I would likely never discuss poetry without the Poetry Box so thank you for this gift!”

Today, some may be frosting cookies to set on a plate by the fireplace for when Santa descends. The custom may continue each year, long after the children have left for college. Many families either follow established traditions or stumble on to their own, without realizing a little habit or ritual grows like a child whose appetite wants feeding.

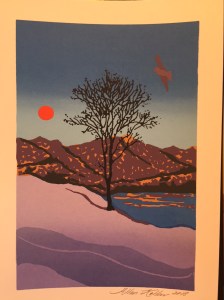

Today, some may be frosting cookies to set on a plate by the fireplace for when Santa descends. The custom may continue each year, long after the children have left for college. Many families either follow established traditions or stumble on to their own, without realizing a little habit or ritual grows like a child whose appetite wants feeding. Influenced by the etchings of Rembrandt, Allan drew an elysian image of a descending angel, etched it in a metal plate, and ran twenty-five original prints for those to whom we wanted to send our Christmas greeting. We made no commitment to ourselves or to others that there would be another the following year.

Influenced by the etchings of Rembrandt, Allan drew an elysian image of a descending angel, etched it in a metal plate, and ran twenty-five original prints for those to whom we wanted to send our Christmas greeting. We made no commitment to ourselves or to others that there would be another the following year. Inevitably, we needed to trust the reproducing work to a professional with a large studio. Allan still creates the image and cuts the stencils before passing on the stencils to Tori, our third professional printmaker.

Inevitably, we needed to trust the reproducing work to a professional with a large studio. Allan still creates the image and cuts the stencils before passing on the stencils to Tori, our third professional printmaker. Then there is the Washington Athletic Club group. What started as a small gathering of early-morning athletes celebrating a Holiday Season breakfast, grew to sixty strong. Gordy dresses as Santa. After handing out our cards, Allan describes the artistic process, and acknowledges the fellowship of starting each day with a workout among friends. I read the poem aloud. Each year, we wonder if maybe we should forego the task of contacting catering, renting a room, taking sign-ups in the locker rooms. But each year, club members ask, “What is the date of this year’s breakfast? We love that tradition.” Suspending a “Tradition” can feel like desertion.

Then there is the Washington Athletic Club group. What started as a small gathering of early-morning athletes celebrating a Holiday Season breakfast, grew to sixty strong. Gordy dresses as Santa. After handing out our cards, Allan describes the artistic process, and acknowledges the fellowship of starting each day with a workout among friends. I read the poem aloud. Each year, we wonder if maybe we should forego the task of contacting catering, renting a room, taking sign-ups in the locker rooms. But each year, club members ask, “What is the date of this year’s breakfast? We love that tradition.” Suspending a “Tradition” can feel like desertion.