A late September afternoon, I am walking home through Volunteer Park, past the playground, quiet as expectation now that children are back to school. Swings, slides, and sculptures for climbing stand silent midst a leaf-spotted lawn that borders Seattle’s historic Lakeview Cemetery. A chain link fence separates a high swinging child and rows of manicured tombstones, many erected in homage to the settlers who first populated our city with Gold Rush, timber-eager adventurers. Pausing before a limp swing lit with early autumn light, I am back seventeen years, lifting my toddler grandson into the swing, then swooshing the boy and swing for a high cemetery view. When both of us are ready to proceed to the slide, my grandson tells me, “I know, Nana, how all those people died.”

A late September afternoon, I am walking home through Volunteer Park, past the playground, quiet as expectation now that children are back to school. Swings, slides, and sculptures for climbing stand silent midst a leaf-spotted lawn that borders Seattle’s historic Lakeview Cemetery. A chain link fence separates a high swinging child and rows of manicured tombstones, many erected in homage to the settlers who first populated our city with Gold Rush, timber-eager adventurers. Pausing before a limp swing lit with early autumn light, I am back seventeen years, lifting my toddler grandson into the swing, then swooshing the boy and swing for a high cemetery view. When both of us are ready to proceed to the slide, my grandson tells me, “I know, Nana, how all those people died.”

“How?” I ask, accustomed to his surprising perceptions.

“All those big stones fell on them.”

Well into my grandson’s nineteenth year, I have retold that story to my grandson and the entire family, so it is a chapter in our book of family humor and nostalgia. However, this morning, the passive swing not only reminds me of the funny story. I actually feel his three-year-old self is forever in that swing. Were he to ask, “Nana, push me,” I would not be surprised.

Well into my grandson’s nineteenth year, I have retold that story to my grandson and the entire family, so it is a chapter in our book of family humor and nostalgia. However, this morning, the passive swing not only reminds me of the funny story. I actually feel his three-year-old self is forever in that swing. Were he to ask, “Nana, push me,” I would not be surprised.

Here in my seventh decade, many of my waking moments exist in multiple time zones. It is a multi-tasking of the mind. I am here at my computer typing away at this blog, while I am simultaneously surrounded by humming electric typewriters in my high school keyboard class, learning to use ten fingers to travel between adjacent keys. I am in that 16-year-old body.

Is living in multiple time zones common? If so, is it more common with older people? This capability to exist mentally in various places at once, is it unique to humans? Is it the same thing as memory? Of course, memory is essential.  Don’t tell me animals live only in the present with no vital memories. When it is time for us to go to our cottage, and we take out the cooler from the basement, our cats disappear. They know the cooler means travel, equals kitty carriers, equals confinement. We must put them in their carrier before even thinking of fetching the cooler. Yet remembering and simultaneous existence are not the same.

Don’t tell me animals live only in the present with no vital memories. When it is time for us to go to our cottage, and we take out the cooler from the basement, our cats disappear. They know the cooler means travel, equals kitty carriers, equals confinement. We must put them in their carrier before even thinking of fetching the cooler. Yet remembering and simultaneous existence are not the same.

The brain has many rooms to visit, and with age, I find the doors are often left open. For about five years, every month I visited Florence Cotton, a long-time member of our church whose age and infirmities prevented her from attending services. In her 100th year, she acquiesced to moving into an assisted living home. Because I asked how she liked her new residence, she told me that there were many programs there she wanted to attend; however, she often missed them for falling asleep in her chair. A woman who always sought the bright side of disappointments, Florence went on, “But it isn’t all bad. Even though I sleep many more hours now, in my sleep I visit friends and family I had forgotten I knew. They show up just the way I knew them at a certain time of my life.” She savored her time travel.

Simultaneous existence can also be painful. My friend Molly tells me about the day she got up to go to school and found no breakfast waiting, but her mother crying. Her beloved brother died in a car accident while young Molly slept. Decades later, remembering the day with another brother, she said they both began to cry, feeling again their loss as if for the first time.

For me, time has never been linear.  It circles around itself like a whirlpool in a pond, gathering newly dropped leaves as it turns. We are brought back around as we proceed forward. Have you heard the declaration, “I don’t want to go there?” I have. The sentence suggests a benefit to burying the past. Understood, as a way to avoid adversity, but today I am thinking that having lived through so many experiences with so many people, I am in a position to live in two or more places at once, and thus able to be more empathic with others who may be experiencing something for the first time.

It circles around itself like a whirlpool in a pond, gathering newly dropped leaves as it turns. We are brought back around as we proceed forward. Have you heard the declaration, “I don’t want to go there?” I have. The sentence suggests a benefit to burying the past. Understood, as a way to avoid adversity, but today I am thinking that having lived through so many experiences with so many people, I am in a position to live in two or more places at once, and thus able to be more empathic with others who may be experiencing something for the first time.

H.G. Wells, and other futuristic writers, embrace time travel. It isn’t a space ship experience where we go to the moon and beyond. Time travel is a ferris wheel circling in the amusement park of life.

Today, some may be frosting cookies to set on a plate by the fireplace for when Santa descends. The custom may continue each year, long after the children have left for college. Many families either follow established traditions or stumble on to their own, without realizing a little habit or ritual grows like a child whose appetite wants feeding.

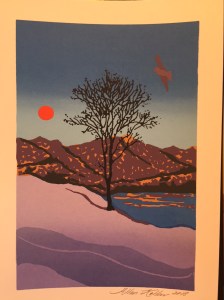

Today, some may be frosting cookies to set on a plate by the fireplace for when Santa descends. The custom may continue each year, long after the children have left for college. Many families either follow established traditions or stumble on to their own, without realizing a little habit or ritual grows like a child whose appetite wants feeding. Influenced by the etchings of Rembrandt, Allan drew an elysian image of a descending angel, etched it in a metal plate, and ran twenty-five original prints for those to whom we wanted to send our Christmas greeting. We made no commitment to ourselves or to others that there would be another the following year.

Influenced by the etchings of Rembrandt, Allan drew an elysian image of a descending angel, etched it in a metal plate, and ran twenty-five original prints for those to whom we wanted to send our Christmas greeting. We made no commitment to ourselves or to others that there would be another the following year. Inevitably, we needed to trust the reproducing work to a professional with a large studio. Allan still creates the image and cuts the stencils before passing on the stencils to Tori, our third professional printmaker.

Inevitably, we needed to trust the reproducing work to a professional with a large studio. Allan still creates the image and cuts the stencils before passing on the stencils to Tori, our third professional printmaker. Then there is the Washington Athletic Club group. What started as a small gathering of early-morning athletes celebrating a Holiday Season breakfast, grew to sixty strong. Gordy dresses as Santa. After handing out our cards, Allan describes the artistic process, and acknowledges the fellowship of starting each day with a workout among friends. I read the poem aloud. Each year, we wonder if maybe we should forego the task of contacting catering, renting a room, taking sign-ups in the locker rooms. But each year, club members ask, “What is the date of this year’s breakfast? We love that tradition.” Suspending a “Tradition” can feel like desertion.

Then there is the Washington Athletic Club group. What started as a small gathering of early-morning athletes celebrating a Holiday Season breakfast, grew to sixty strong. Gordy dresses as Santa. After handing out our cards, Allan describes the artistic process, and acknowledges the fellowship of starting each day with a workout among friends. I read the poem aloud. Each year, we wonder if maybe we should forego the task of contacting catering, renting a room, taking sign-ups in the locker rooms. But each year, club members ask, “What is the date of this year’s breakfast? We love that tradition.” Suspending a “Tradition” can feel like desertion.

How many Snicker Bars or Peanut Butter cups does one child need? Does any child remember what house gives out Milk Duds and which Nestles Crunch? Little distinction, even less distinction in flavor or freshness. Super markets shove bags of Halloween candy on their shelves in late August.

How many Snicker Bars or Peanut Butter cups does one child need? Does any child remember what house gives out Milk Duds and which Nestles Crunch? Little distinction, even less distinction in flavor or freshness. Super markets shove bags of Halloween candy on their shelves in late August. Below them we dumped the unfamiliar, and therefore suspect, sopping honey confection. My adult self longs to return to the front door to be given a second chance. From many houses we got apples, always apples, barely welcomed in our greed for sweets. Mom separated them out from our Trick or Treat bag, parsing them out for school lunches. She also saved the nickels given by those unprepared to bake. Once there was a quarter among the change.

Below them we dumped the unfamiliar, and therefore suspect, sopping honey confection. My adult self longs to return to the front door to be given a second chance. From many houses we got apples, always apples, barely welcomed in our greed for sweets. Mom separated them out from our Trick or Treat bag, parsing them out for school lunches. She also saved the nickels given by those unprepared to bake. Once there was a quarter among the change.

I borrowed my brother’s leather cowboy vest, redolent with his own sweat that I identified with horse flesh. His cap gun hung heavily from my non-existent hips. If I were lucky, he would share a red roll of caps, their explosive pops filling my lungs with sweet sulfur.

I borrowed my brother’s leather cowboy vest, redolent with his own sweat that I identified with horse flesh. His cap gun hung heavily from my non-existent hips. If I were lucky, he would share a red roll of caps, their explosive pops filling my lungs with sweet sulfur. It is only an occasional child, usually a young one, who has changed identity for the night, who growls like the furry beast it is. I long for role-playing, for the ferocious tiger who will dare me to open the door wider. I hold out the wide wooden bowl brimming with mini Snickers and Tootsie Pops. Each year the packages shrink, but the kids don’t seem to notice. Their plastic pumpkin carriers are brimming with replicas of what we are giving. Over their shoulders, the little monsters thank us as they race back down the stairs to the sidewalk where an adult or two waits to escort them to the next house. As they secure their children’s sticky hands, does their tongue remember the taste of their own childhood? Gone are the days when children ran out the front door as soon as dusk swallowed the maple trees, to tag along with older siblings, combing the darkening streets until the soiled pillow case, filled with treats, weighed them down. Then it was time to return home to parents, unconcerned about absence after dark, sitting by a lamp reading until their costumed children had played out their one-night characters and were ready for sweetened sleep.

It is only an occasional child, usually a young one, who has changed identity for the night, who growls like the furry beast it is. I long for role-playing, for the ferocious tiger who will dare me to open the door wider. I hold out the wide wooden bowl brimming with mini Snickers and Tootsie Pops. Each year the packages shrink, but the kids don’t seem to notice. Their plastic pumpkin carriers are brimming with replicas of what we are giving. Over their shoulders, the little monsters thank us as they race back down the stairs to the sidewalk where an adult or two waits to escort them to the next house. As they secure their children’s sticky hands, does their tongue remember the taste of their own childhood? Gone are the days when children ran out the front door as soon as dusk swallowed the maple trees, to tag along with older siblings, combing the darkening streets until the soiled pillow case, filled with treats, weighed them down. Then it was time to return home to parents, unconcerned about absence after dark, sitting by a lamp reading until their costumed children had played out their one-night characters and were ready for sweetened sleep.