Having paid for my coffee and scone, I seek a favorite corner table at the Volunteer Park Café. It is one of two tables by a front window with a view to the orange leaves of a sweet gum tree and a sidewalk café table under its autumnal branches. It is 7:00 AM on an October morning, the first rainy day of many to follow, so the café lights hold us warmly inside, and with the darkness outside, I cannot see the tree I usually enjoy. At the table beside me, sits a woman in her 30’s, checking her I-Phone until she looks up to welcome another woman, perhaps a decade older, her hair graying in a stylish bob. The newcomer hangs her rain jacket on the chair, slips her umbrella under the table, and the two of them begin talking before she sits down. Although I am close enough to eavesdrop, I don’t intrude, and besides, I can infer by their exchange, the way they lean in to their shared space — gesturing and taking turns as they speak –that they are helping each other through some little thing.

“That is what friends do,” I think, “especially women friends.” They tell stories about what happened, and to confirm the friend has listened sympathetically, the other tells a similar story. Two stories are better than one. One of the stories echoes the veracity of the other. Are women naturally narrators, or do we tell stories on ourselves to confirm those told by our friends? Is it a kind of “group think?”

Later in the morning I meet with a woman I have known for twenty-five years. She asks to meet with me to discuss a sadness in her life for which she believes I might have a shared experience. We have family and friends in common, and they are the subject of her grief. First, we catch up on little things we do to fill our days. Then, testing a shared comfort, she begins to tell her personal story of a loss she experienced years before we met. She pauses. Because I know the Girl Talk script, I sense she is waiting for me to tell of my own loss years before we met. From our stories, there might not arise exact similarities, but there will be a kind of universality of experience that brings understanding to a sad occurrence. People seek reasons for their pain, but will settle for parallels, if reasons can’t be found.

Later in the morning I meet with a woman I have known for twenty-five years. She asks to meet with me to discuss a sadness in her life for which she believes I might have a shared experience. We have family and friends in common, and they are the subject of her grief. First, we catch up on little things we do to fill our days. Then, testing a shared comfort, she begins to tell her personal story of a loss she experienced years before we met. She pauses. Because I know the Girl Talk script, I sense she is waiting for me to tell of my own loss years before we met. From our stories, there might not arise exact similarities, but there will be a kind of universality of experience that brings understanding to a sad occurrence. People seek reasons for their pain, but will settle for parallels, if reasons can’t be found.

Perhaps others around us might think we are gossiping. It is sad that even in Shakespeare’s plays, women are portrayed as Gossips. The word Gossip itself, when used as a noun instead of a verb, implies a woman, usually an old woman. So much literature and art tells or shows women in confidences sharing those stories, usually about others in the community. Gossiping suggests the stories are negative. Rather than telling a story to arrive at some truth, the Gossip tells stories to denigrate another or elevate herself by juxtaposition. “Did you hear that Maggie Jones spent $500 dollars of her husband’s social security check on new shoes?”  Gossiping is inherently judgmental, and I regret that it is more often associated with women. But men gossip too. They tell about a business rival who cheats on his income tax. Men’s Sports Gossip (sometimes referred to as “Locker Room Talk”) can be as rough as the sports they discuss.

Gossiping is inherently judgmental, and I regret that it is more often associated with women. But men gossip too. They tell about a business rival who cheats on his income tax. Men’s Sports Gossip (sometimes referred to as “Locker Room Talk”) can be as rough as the sports they discuss.

Another common perception of Girl Talk, is that women talk more than men. That seems situational. When with their own gender, women may speak rapidly. There is a delight, like a bubbling fountain, when two female friends discuss the best way to do something they both love, such as reading fiction, or when they are sharing complaints from work or home. When in mixed company, I find women speak less frequently, or turn away from men, to carry on a separate conversation with other women present. It wasn’t that long ago when after formal dinners, women were escorted to the parlor for music or knitting so that men could converse civilly in their absence. The male talk was to be more serious and consequential than what concerned the women in the parlor. Certainly, the masculine talk was more consequential, because white men held all the power. Why share it with the powerless?

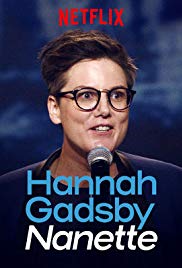

When women talk, they are expected to keep their voices soft, at least softer than men are permitted to speak. If women speak loudly or aggressively, they are called “shrill.” I have never heard a man’s talk referred to as shrill. At best, angry. Women are not expected to express anger. It somehow lessens the power of their message. Recently our daughter suggested we watch Nanette: Comedy Hour on Netflix.  The stand-up comedian, Hannah Gadsby from Tasmania, based her humor on the awkward lives of lesbian women. A lesbian herself, she told about her own experiences suffering criticism and misunderstanding. As the show continued, what was at first humorous, became tragic. Annoyance grew to righteous indignation. What she said was no longer funny. The show was, however, profound. My husband didn’t enjoy the show, because of Hannah’s expressed anger, even though he sympathized with her many grievances. If she had spoken softly and slowly, her voice not pitched in indignation, I wonder if he would have more readily accepted the truths she offered.

The stand-up comedian, Hannah Gadsby from Tasmania, based her humor on the awkward lives of lesbian women. A lesbian herself, she told about her own experiences suffering criticism and misunderstanding. As the show continued, what was at first humorous, became tragic. Annoyance grew to righteous indignation. What she said was no longer funny. The show was, however, profound. My husband didn’t enjoy the show, because of Hannah’s expressed anger, even though he sympathized with her many grievances. If she had spoken softly and slowly, her voice not pitched in indignation, I wonder if he would have more readily accepted the truths she offered.

Women and narrative are one. The process is not quantitative. Years ago, when the UW physics department bemoaned the lack of women enrolled in their classes, they researched the differing ways men and women learn, hoping to find an answer there. They did. Women are more than twice likely to learn something through a story than are men. Facts alone won’t stick. Women are more attracted to a subject embedded in narrative.

There is no more dramatic illustration of the power of Girl Talk than the #MeToo Movement. The conversations do not stop with “Me Too, I too was harassed or raped.” The talk continues, “And this is what happened, and this is who did it, and this is what I want now.” The stories pour out from abused women, not merely for retribution or even for justice, though both are needed. The stories are also for healing. Carrying unspoken stories is like dragging around a stuffed suitcase of clothes so old and worn you wouldn’t be seen in them in public. Telling the stories, one old coat after another is cast away, leaving the abused woman weightless, ready to wear a new story that fits comfortably, perhaps helping her feel attractive for the first time.

“So get to the point,” my husband said yesterday while I was telling him a story about my day. We were driving in heavy traffic, late to meet friends for dinner. He was trying to concentrate, while I was talking in my circular way about my day. But when he said, “So get to the point,” I wanted to protest. For me, it wasn’t the point that mattered, but the process of telling the story. Some of my stories intertwine with others, so I cannot just slide down them like a rope that ends in a coil of understanding. The unfolding of the story is as important as the point, if there is a point at all. There need not be one, or there may be many. In the process of telling, I may find a point I didn’t know the story possessed. Meanwhile, let me tell it. Let me tell it my way.

Don’t cut me out of the story. In my parents’ life, there had been a series of infidelities by my father when he was in India in WW II. All my life, I intuited my mother’s distance and lack of intimacy with him when he returned to the States. I stumbled across photos of unfamiliar women in a jeep in Delhi, another, a woman sitting on an army truck, her legs crossed so her skirt rode high on her thighs. My mother did not remove those photos from the album. Only in the year before she died, when I took my now-widowed mother for a weekend on the Oregon coast, did she tell me some of the story, of her loneliness back in Iowa with three children, of letters my father sent suggesting their marriage might end when he returned. They did not divorce, by the way, although I think my mother’s life may have been better had they separated. Because she finally told me the story behind those photos, my heart was less heavy than it had been throughout my childhood. I was in no better place to repair her life, but her story with that history, helped me experience our mutual love.  . And there you are — all stories are love stories, because through them we bond as we walk along the tangled paths of our human condition.

. And there you are — all stories are love stories, because through them we bond as we walk along the tangled paths of our human condition.

So true, so true. Right now, my parallel story is the women’s breakfast table at the senior housing where I recently moved. In the large dining hall, there is one long table set for eight, and, over the course of an hour or so, women come to eat and when they leave are replaced by other women who arrive to eat at a later time. In course of a morning, I converse with 12-14 women, often staying for a third cup of tea so that we can finish our stories. We talk about past hardships, good times, and our strategies for adjusting to living in a “facility.” We check in on each other’s health and plans for the day. A few of the men residents have told me they are puzzled about the “women’s table.” One observed that we “all seem to be talking at once and yet understanding everything being said.” Perhaps I should show them your blog?

LikeLike

I know that Girl Talk has strengthened me throughout my life. My group of “girls” includes some from first grade, some from various groups I’ve joined over the years, some brand new ones…and even the “one off” ones that I meet at an event. We seem to know how to connect and feel stronger once we have. Thanks, Mary, for writing this!

LikeLike

Thanks Kathryn. We have all grown stronger together

LikeLike

I love the story about the cafe and the wonderful photos. I feel as if I’m sitting at the table with you observing the women helping each other through conversation. I am keenly aware of the difference in conversation style between myself and my husband. He tells stories skipping details to get to the point. I ask him questions for a fuller story but his reply is always the same: “I don’t remember, I don’t do details.” I suspect that men in this culture have a tendency to sort through details in their head to get to the point. Women, on the other hand, use conversation to weigh options and organize thoughts which may or may not lead to a point. In most cultures, men are valued because they are men. Women feel valued when they are heard, and with each conversation our voices grow stronger.

LikeLike

Mary, this is so good and true and sometimes we just need to be reminded how important our stories are and not only that–but the WAY we tell our stories is important too. “Let me tell it my way.” Perfect. Amen. Thanks for this.

LikeLike