Last year, a group of my longtime women friends gathered for an every-two-month Zoom chat. Joined in friendship for having exercised between 5:30 and 7:00 AM at the Washington Athletic Club, and having shared the same mirror for applying make-up before heading off to various jobs, we remained friends through ensuing decades and retirement. Now we exercise in Seattle, Sacramento, Billings, Newport – all separated from the communal mirror, but we remain a supportive group, encouraging one another as we move past “significant” birthdays. It was while we were cheering on Sylvia, walking across her 80-year milepost, when we recalled all she had done in her productive life, yet also what she had not done. In all of her eighty years, Sylvia had not attended a rock concert.

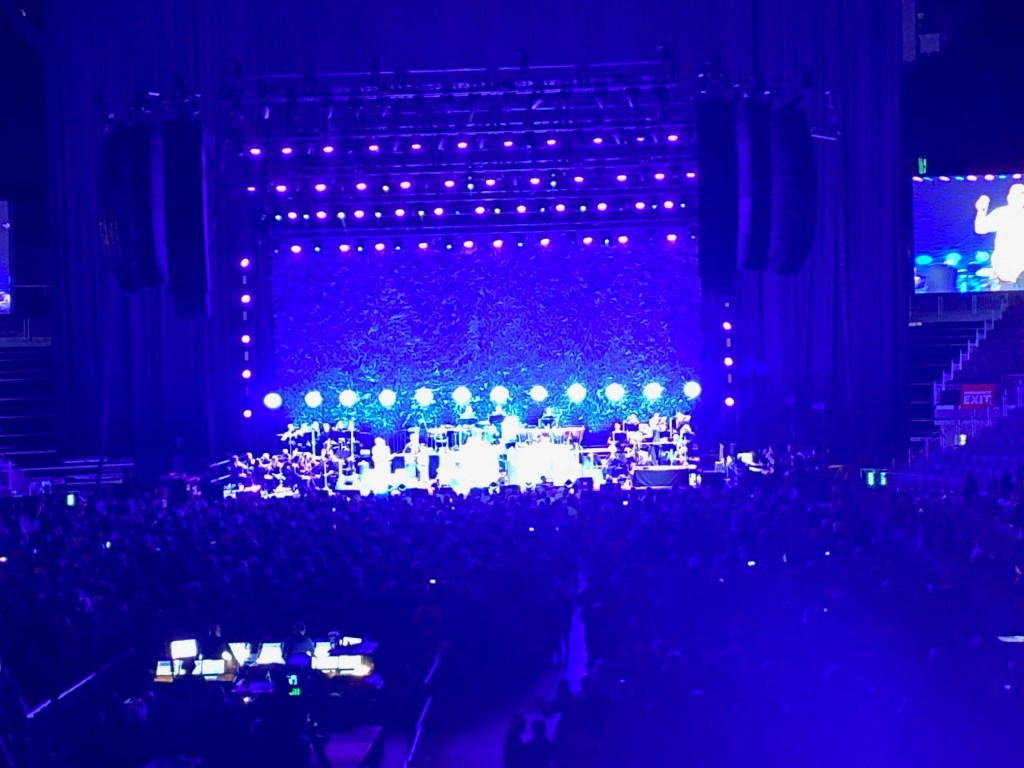

“That’s it,” Nikki chimed in. “We have to take Sylvia to a rock concert, a critical item for her bucket list.” Sylvia has been a parent, wife, Director of Children and Family Services for the State of California, just one of many social agencies she headed up. There isn’t much Sylvia has failed to accomplish nor experience. Yet, within minutes, the group was assigning each other to locate accessible rock concerts that would not involve too much travel or expense, and then to acquire tickets. We settled on The Who, a rock-concert scheduled a year down the road in Seattle’s newly refurbished Climate Pledge Arena. Since some of us still live in Seattle, we could host those who had moved away. Perhaps committing to such a distant date made it easier for me to go along, not being inclined to expose myself to decibels of ear shattering instruments nor crowds of baby boomers trying to rock back into their teens. I agreed to go, because it would mean a weekend with my dear friends, women with whom I share a history.

Here I am, having survived the rock concert, yet still reflecting on the notion of a bucket list. I sought out Wikipedia for a definition, even though it is a common idiom made popular by the Jack Nicholson/ Morgan Freeman movie. We know it evolves from the phrase “kick the bucket,” ie. die. And “kicking the bucket” for death goes back to the 1700’s when it may have referred to a condemned man standing on a bucket before the gallows. When the bucket was kicked out from under him, the noose gripped and ……

A bucket list is a list of experiences one hopes to experience before death. But why? What is there about our society that expects death to be more palatable if it is preceded by a life filled with random experiences: travel, childbearing, financial success, sports, hobbies , attending rock concerts? Or is having a bucket list a way of forestalling death? “Can’t go now, Grim Reaper. I have a rock concert to attend.”

The bucket list allows a forward gaze. Who doesn’t like to have something for which we can look forward? Yet let’s look at the attendance at the Who concert. There were no teenagers jumping, waving arms, throwing themselves on the stage. Surely there were teenagers in the audience, but many were brought along by their parents or grandparents. From where we sat mid-center across from the lights flashing on stage, I have not seen so much gray hair — gray hair for those who still had hair. I should confess here that although I was vaguely aware of the Who in the 1970’s, I was preoccupied as a single parent with a toddler and teaching high school, so that I was oblivious to popular music beyond the Beatles. Yet there I sat surrounded by folks my age who were mouthing lyrics I could not discern through the amplification while they thrust out their arms in remembered gestures that accompanied those songs, gestures made when both the Who and the audience were much younger. The opposite of looking forward, is looking backwards. Surely, we were looking both ways.

Americans are proudly always on the move. I have the attention span of fly in a sugar factory, so I understand this split between “the good old days,” and “what’s next?” Yet one of the benefits of aging is the way the body slows down. How comforting to do nothing but sit, observe, feel. In Milton’s sonnet “On His Blindness,” Milton despairs that his fading eyesight prohibits him from writing; whereas writing was his vocation, literally his calling to serve God. After bemoaning his blindness in the first eight lines of the poem, Milton arrives at an understanding that God doesn’t need Milton’s gifts, that “Those also serve who only stand and wait.” I keep that line in my pocket, even when stuck in a sluggish line at a grocery store. How obsessed I can be with Chronos, with sequential time, years passing; whereas, Kairos focuses on qualitative time. Was the Rock Concert important to do before death? Certainly not, but qualitative time with my friends is a treasure.

Japanese Tea House. Arboretum, Seattle