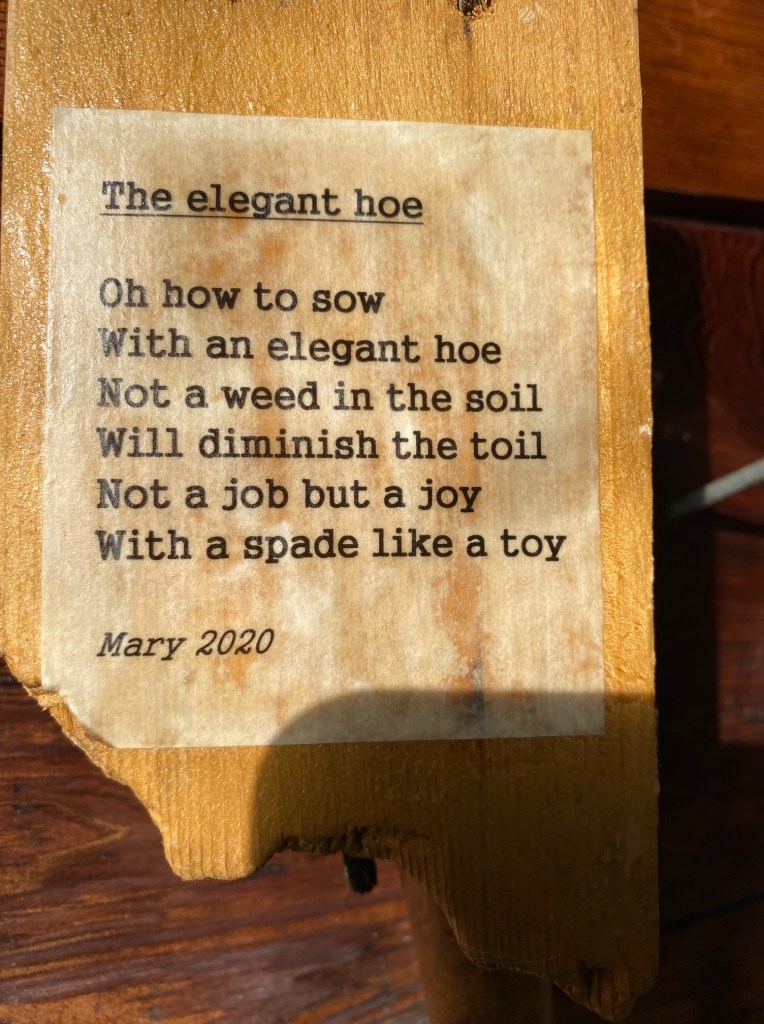

Hanging on a leather strip from a nail on the greenhouse wall is a hand spade, its handle wood, its blade a fierce copper designed to uproot the most determined weed. Rewarding my passion for gardening, my brother gave it to me for my birthday. The spade is a more sophisticated tool than I would have purchased for myself, and so I wrote him a thank-you poem, which he, in turn fashioned on a wood slab to hang alongside his gift. How often tools bring us together.

In a tidily organized drawer in the garage, my husband stores his father’s tools: a skill hand drill, several wood planes and specialty hand saws. His father was a finished carpenter whose tools have long since been improved on by technology. Nevertheless, my husband stores those tools with the same reverence he has for any memento of his father’s life.

His dad’s lessons endure in the storage shed adjacent to the greenhouse where my husband has affixed wooden pegs in measured spaces one from the other to line up all sorts of gardening implements: hedge clippers, shovels, rakes, each in its place. When my sister-in-law visited and spied what her brother had organized, she laughed out loud at the reincarnation of their father’s devotion to his tools. Like father, like son, you might conclude, but surely no different than my daily use of a small cutting board once belonging to my mom. Why have I not replaced it with a larger one? You know why.

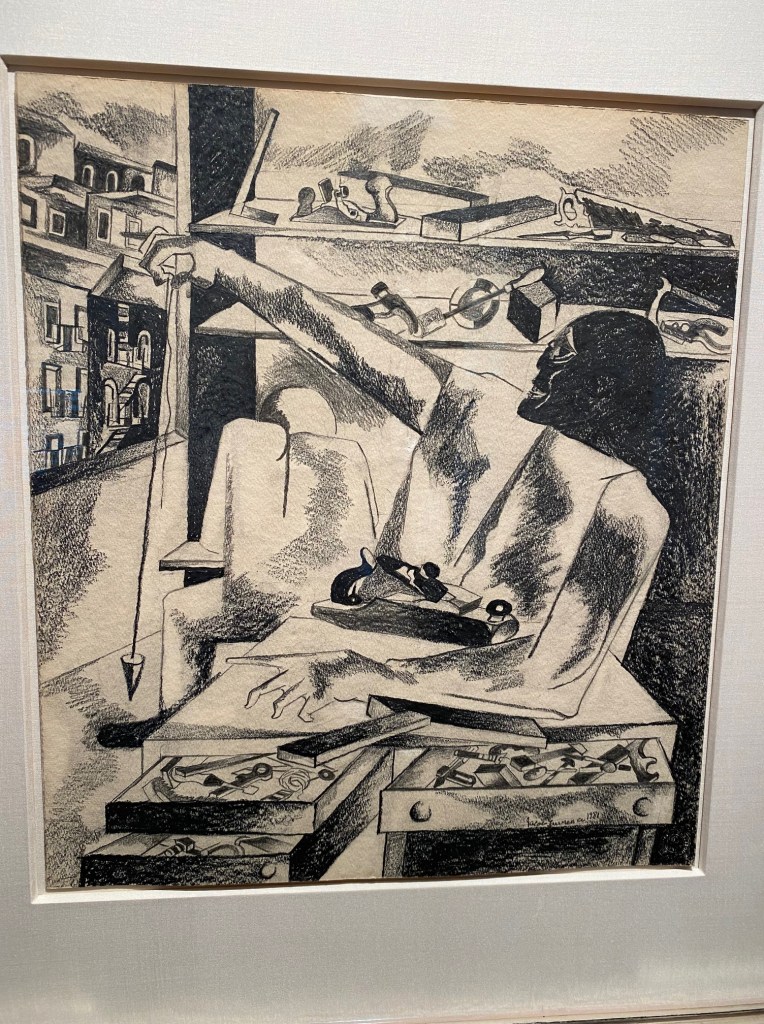

Tools are extensions of ourselves – the paintbrush to Monet, the baton to Leonard Bernstein. Tools can be the measurement of our lives. The artist, Jacob Lawrence, was not a builder, but his paintings and prints are full of tools — tools, hanging, tools overflowing in drawers. We are fortunate to own a self-portrait Lawrence drew of himself in the later years of his life. In the portrait, he sits before an open window in his Seattle studio surrounded by tools. In his hand he holds a plumb line up to the window while looking over his shoulder at Harlem from which he came. A plumb line is an essential tool for a builder because it works with gravity to assure things are aligned. Is Jacob Lawrence reflecting on the journey of his life, looking back to see if his course has been true? As a symbol of measurement, the plumb line occurs more than once in the Bible. In the book of Amos, the Lord explains his judgement to Amos: “I am setting a plumb line among my people Israel: I will spare them no longer.” (Amos 7: 7-8)

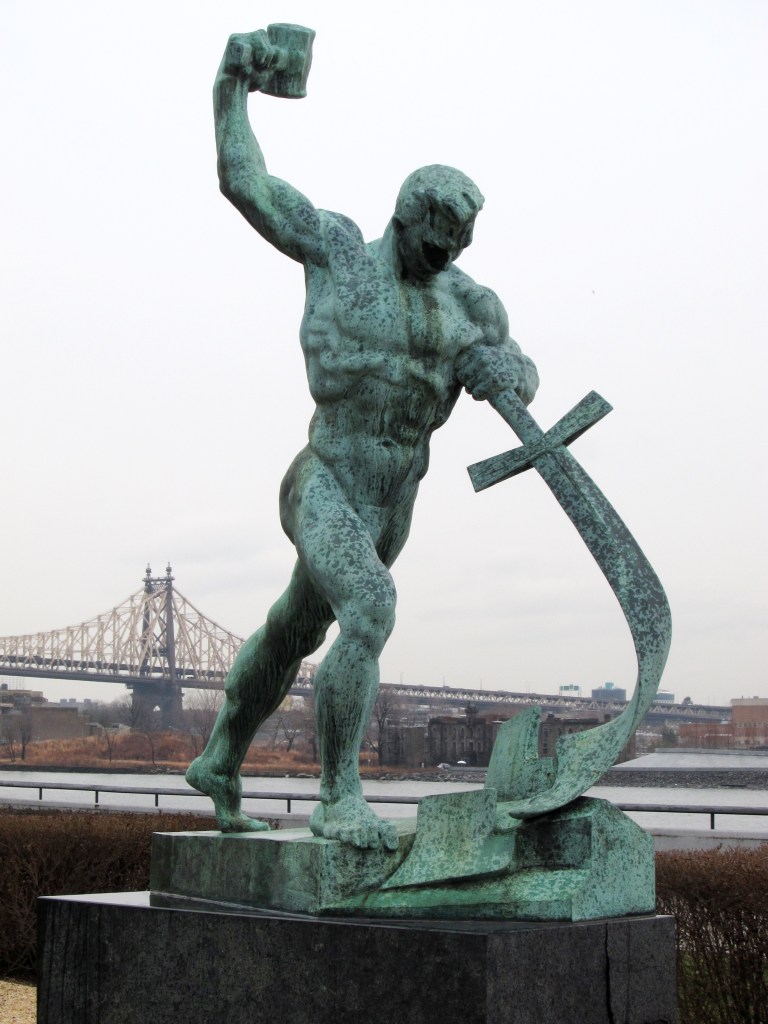

Although we most often think of tools as creative instruments, the Smithsonian Institute has an exhibition of Civil War weapons it calls The Tools of War. The Bible has much to say about those tools as well. In Micah 4:3, it is written, “He shall judge between many peoples, and shall arbitrate between strong nations far away; they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.” Even as I copy this quotation, my mind moves to the Middle East and to Ukraine. What more can I say that is not already in our hearts? Here is a photo of a sculpture in the garden of the United Nations, a work of art by Yevgeny Vuchetich, a 1959 gift of the Soviet Union to the United Nations. The title is: Let Us Beat Swords Into Ploughshares. Surely ironic today.

The poet, Robert Frost, was always ready to see cruel ironies:

Objection to Being Stepped on:

At the end of the row

I stepped on the toe

Of an unemployed hoe.

It rose in offense

And struck me a blow

In the seat of my sense.

It wasn’t to blame

But I called it a name.

And I must say it dealt

Me a blow that I felt

Like a malice prepense.

You may call me a fool,

But was there a rule

The weapon should be

Turned into a tool?

And what do we see?

The first tool I step on

Turned into a weapon.

Summer nights we drive with the guys to cranberry bogs where the boys take.22 gage rifles from the car’s trunk and aim them out toward the bogs where frogs have stilled their songs. Then the guns fire, the shooters gleefully enjoying the sight of frog parts exploding among the cranberries. Easy, fear-frozen targets for reckless teenagers.

Summer nights we drive with the guys to cranberry bogs where the boys take.22 gage rifles from the car’s trunk and aim them out toward the bogs where frogs have stilled their songs. Then the guns fire, the shooters gleefully enjoying the sight of frog parts exploding among the cranberries. Easy, fear-frozen targets for reckless teenagers.  Here in the Pacific Northwest, in March, Nature’s early promise of spring comes with frog song from the pond and surrounding woods. Weeks before robins, chickadees and violet-green swallows take up their warbling sopranos, the bass line is sung by frogs caroling for potential mates from misty dawn until dusk.

Here in the Pacific Northwest, in March, Nature’s early promise of spring comes with frog song from the pond and surrounding woods. Weeks before robins, chickadees and violet-green swallows take up their warbling sopranos, the bass line is sung by frogs caroling for potential mates from misty dawn until dusk. How can we value those songs we take for granted, knowing they are not our own, but somewhere around us in the vernal woods and waters that we treasure?

How can we value those songs we take for granted, knowing they are not our own, but somewhere around us in the vernal woods and waters that we treasure?

![IMG_0423[1]](https://thoughtsafterseventy.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/img_04231.jpg?w=764) Peter Pan met Wendy when he came to ask her to sew his shadow back in place, having lost it when escaping through a window that closed, separating himself from his other half.

Peter Pan met Wendy when he came to ask her to sew his shadow back in place, having lost it when escaping through a window that closed, separating himself from his other half.  Detaching from our shadows is a fantastical fright, for what is more intimate and yet mysterious than our shadow, our companion from the first sunny days of our lives? We watch it grow with our own growth and with the rise or fall of sunlight behind us.

Detaching from our shadows is a fantastical fright, for what is more intimate and yet mysterious than our shadow, our companion from the first sunny days of our lives? We watch it grow with our own growth and with the rise or fall of sunlight behind us.![IMG_0420[1]](https://thoughtsafterseventy.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/img_04201.jpg?w=224) Most days, unmindful of my shadow, I am surprised when I notice it lengthening before me on a spring walk. I notice my aging stance. Did my knee always turn in at a funny angle, or is this something new? Communicating with our shadows is a self-indulgent pleasure .

Most days, unmindful of my shadow, I am surprised when I notice it lengthening before me on a spring walk. I notice my aging stance. Did my knee always turn in at a funny angle, or is this something new? Communicating with our shadows is a self-indulgent pleasure . Sometimes the shadows share importance with the object, as in some paintings by Norman Lundin. His many compositional brilliances that feature shadows cast across classroom blackboards are equally as important as the object or person who cast them. Our admiring eye finds pleasure in the angles of lines across a flat surface.

Sometimes the shadows share importance with the object, as in some paintings by Norman Lundin. His many compositional brilliances that feature shadows cast across classroom blackboards are equally as important as the object or person who cast them. Our admiring eye finds pleasure in the angles of lines across a flat surface.

![IMG_0419[1]](https://thoughtsafterseventy.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/img_04191.jpg?w=224)

No icy fingers reached to pull me inside.

No icy fingers reached to pull me inside.

In any season we hear advice to slow down, pause, notice life unfolding. But like a stern mother whose advice wasn’t heeded, Mother Nature and the Coronavirus have forced us to narrow the circumference of our activity, making time for noticing. In these weeks, the media has elevated poetry to the popularity of rock music. Poets are known to take notice. Forced to touch each other only through cyberspace, we email to our friends, poems, words of wisdom, images of sunrises and blossoms.

In any season we hear advice to slow down, pause, notice life unfolding. But like a stern mother whose advice wasn’t heeded, Mother Nature and the Coronavirus have forced us to narrow the circumference of our activity, making time for noticing. In these weeks, the media has elevated poetry to the popularity of rock music. Poets are known to take notice. Forced to touch each other only through cyberspace, we email to our friends, poems, words of wisdom, images of sunrises and blossoms. For weeks I have passed tight-fisted knuckles in their hearts, for in late winter I had pruned last year’s large, browning fronds. Regardless of my watching, they uncurl in their own time; but I also have last April’s memory of supple green ferns spreading across the hill. Almost May 1st, I am comforted, looking forward to where their funny, twisting dance is going.

For weeks I have passed tight-fisted knuckles in their hearts, for in late winter I had pruned last year’s large, browning fronds. Regardless of my watching, they uncurl in their own time; but I also have last April’s memory of supple green ferns spreading across the hill. Almost May 1st, I am comforted, looking forward to where their funny, twisting dance is going.

When I look outside of my own experience to other women’s lives, I see similar patterns of fulfilling needs for others, mostly domestic needs, that make others’ lives comfortable. Does the fulfilling of those needs enrich the “needed” woman? Would she have chosen the tasks without societal expectation?

When I look outside of my own experience to other women’s lives, I see similar patterns of fulfilling needs for others, mostly domestic needs, that make others’ lives comfortable. Does the fulfilling of those needs enrich the “needed” woman? Would she have chosen the tasks without societal expectation? or she sat before the television watching Murder She Wrote with Angela Lansberry,

or she sat before the television watching Murder She Wrote with Angela Lansberry,

Top on the siren call would be perceived needs from my grandchildren and daughter. My granddaughter, a college senior, emails me a draft of her senior English thesis for editing. Her request leapfrogs to the top of my to-do list, real or imagined. I am flattered to be needed, especially to be needed for something that acknowledges I have a brain, not only a scrub brush.

Top on the siren call would be perceived needs from my grandchildren and daughter. My granddaughter, a college senior, emails me a draft of her senior English thesis for editing. Her request leapfrogs to the top of my to-do list, real or imagined. I am flattered to be needed, especially to be needed for something that acknowledges I have a brain, not only a scrub brush.