Growing up listening to Sunday sermons, not a year passed without the sermon whose message was, “It is more blessed to give than receive.” I got it. Be generous. There are so many people less fortunate than you. God will smile upon your giving with grace.

Then one Sunday, Dr Dale Turner’s sermon was “It is As Blessed to Receive as to Give.” His sermon opened a window to the welcome light of being a gracious receiver. He reframed that common phrase: “Oh really you shouldn’t have!” when someone brings us a gift. To say someone should not have given a gift diminishes the one making the gift. Why? Because in making a gift, the giver has invested thought, perhaps even love. Expressing joy, gratitude, or surprise in receiving that gift, you are returning a spiritual gift-in-kind. “Your gift matters, and you also matter.”

I am going back here many decades, when living in an apartment house with a central courtyard. One Mother’s Day the young moms were sharing social time in that courtyard when five-year-old Kimmie handed her mother a small African violet. “Oh darn,” her mom said, “one more plant I need to water.” I still vividly see Kimmie’s injured look. Likely with no bad intentions, her mom was being witty for the other moms present but disrespecting her child’s gift.

Christmas morning, we gather around the living room, tree lit, fireplace aglow while our three grandchildren distribute gifts they have purchased or made for us. When Max brings me his present wrapped creatively in newsprint or finger-painted paper, he seems to hold his breath while I remove abundant cellophane tape and open the package. After my joyful hug of appreciation, he exhales as if he were swimming underwater until he could experience my reaction.

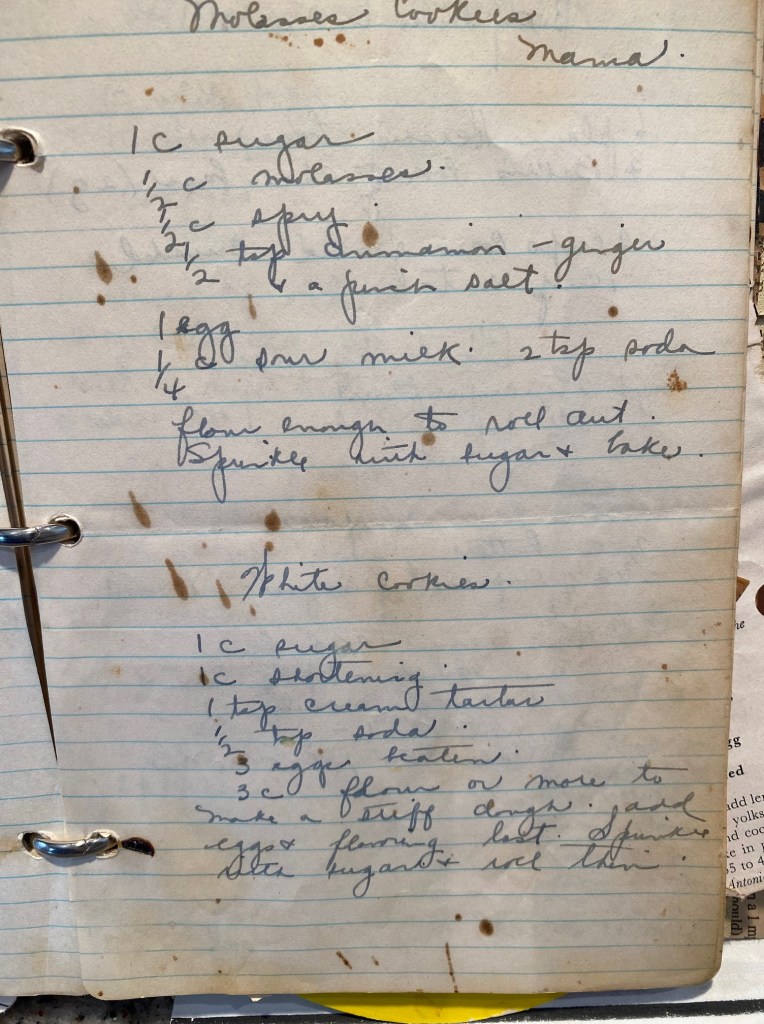

Each fall, when relatives ask what we would like for Christmas, we say, “We don’t need a thing,” and that is true. I imagine one more kitchen device I have no room to store, and I beg off with “Let’s just send consumables this year.” I make raspberry jam to send and await my sister-in-law’s Ukrainian cookies. One step from there is “Let’s just do cards this year.” Both sides agree. Then a week before Christmas, a beautifully wrapped box arrives from my brother and sister-in-law with a card that reads. “a gift for the cook.”

I feel bad, because I had sent only jars of homemade strawberry jam. What happened to our agreement for only consumables? To relieve my feelings of remorse, I head for the computer, go online and order something in return, hoping it will arrive before Christmas. I look for something I think my sister-in-law will enjoy and may not already own. I am happy when I think I found a good gift. It doesn’t take a degree in psychology to conclude that my actions may be less about a gift for my sister-in-law than a way to relieve the guilt I feel for sending only jam. Surely it was her opportunity to give that matters– a pleasure for her that I might receive with gratitude.

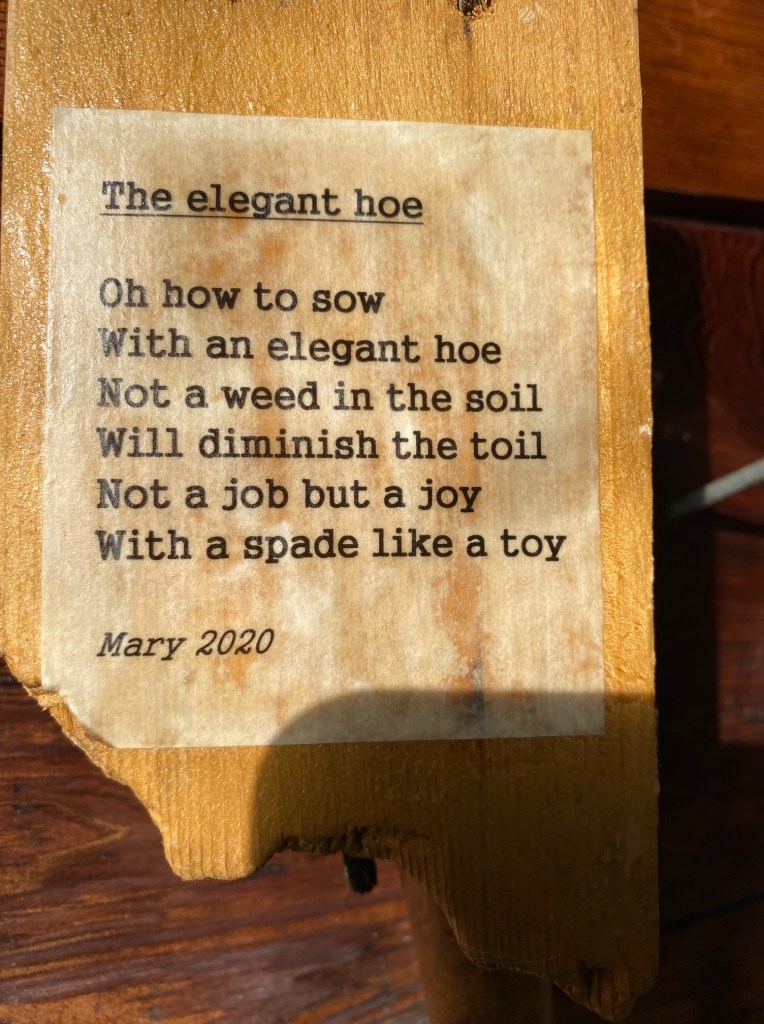

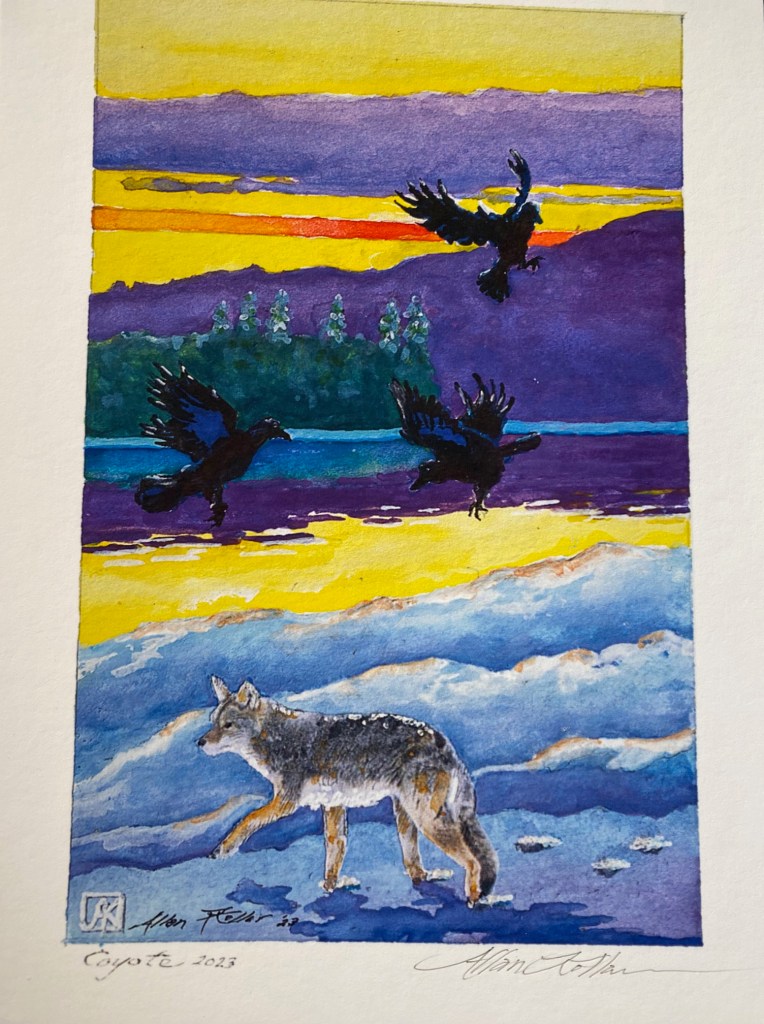

After all, what is a gift but a way to connect? Each year, my husband makes a beautiful art card, a watercolor scene. I pair it with a poem. We have lived so long that our card list is quite long. I joke that the only way one can get off our mailing list is to die. Now at eighty-years-old, I feel the ironic twist. The list is shrinking. Many of those to whom we send the cards do not mail holiday cards. Surely we enjoy the cards we receive, but our receiving cards does not affect our sending the cards out. We devote a whole day to the mailing, and as each name emerges, we have a minute to think about those people, bringing back memories that might not have emerged had we not sat there sending out our little gift. Who is giving this present? Who is receiving the gift?