When I retired from the classroom, my heart felt as if had been tossed on the beach at low tide for the seagulls to pick at what remained of me. Although I knew better, I wondered how next year’s class of Senior English students could be adequately prepared for college by another teacher. These feelings demonstrate either humungous hubris or festering fear. What I have since acknowledged is that I need to be needed. Being needed justifies taking up air and soil from a planet with a paucity of resources.

Only recently have I explored how and by whom these needs are defined. I suspect that many are defined by a patriarchal tradition: making dinner for my husband, doing laundry etc. – all necessities for myself as well.  When I look outside of my own experience to other women’s lives, I see similar patterns of fulfilling needs for others, mostly domestic needs, that make others’ lives comfortable. Does the fulfilling of those needs enrich the “needed” woman? Would she have chosen the tasks without societal expectation?

When I look outside of my own experience to other women’s lives, I see similar patterns of fulfilling needs for others, mostly domestic needs, that make others’ lives comfortable. Does the fulfilling of those needs enrich the “needed” woman? Would she have chosen the tasks without societal expectation?

I reflect on my mother’s life in trying to understand my own. My mother began her typical day setting out sack lunches for her children (if we were still in school), and then making breakfast for all. Soon after, she set off to work as a bank secretary, eventually an “executive secretary” to the manager. Not only did she type his correspondence, she approved loans and managed certain business accounts, jobs that would today earn a title of loan officer, or even vice president, but executive secretary sealed her salary and her prestige. During her lunch hour, she walked across the street to the supermarket to buy groceries for preparing dinner when she got home. After dinner and with dishes put away, she made her “creative time,” either haltingly playing the piano, a treat she afforded herself with biweekly lessons,  or she sat before the television watching Murder She Wrote with Angela Lansberry, who had a startling resemblance to Mother. As my mother did her vicarious sleuthing, she did needlework, usually a square of a quilt painstakingly appliqued or cross stitched. She played piano for no one’s pleasure but her own. Her needlework may have ended in a gift or a practical blanket for a bed, but ultimately, she stitched for the beauty of the thing. At the end of her workday, she fulfilled a call to be needed by herself. Did it also fulfill her to know that her family needed her food, her cleanliness, her salary?

or she sat before the television watching Murder She Wrote with Angela Lansberry, who had a startling resemblance to Mother. As my mother did her vicarious sleuthing, she did needlework, usually a square of a quilt painstakingly appliqued or cross stitched. She played piano for no one’s pleasure but her own. Her needlework may have ended in a gift or a practical blanket for a bed, but ultimately, she stitched for the beauty of the thing. At the end of her workday, she fulfilled a call to be needed by herself. Did it also fulfill her to know that her family needed her food, her cleanliness, her salary?

Our family chuckled at my mother’s devotion to Murder She Wrote. Having recently read Deborah Levy’s The Cost of Living, I can revisit my mother through Levy’s words: “Did I mock the dreamer in my mother and then insult her for having no dreams?”

I considered calling this piece, After the Chores are Done, for that is when Mother’s needs were addressed. That is also when my needs are addressed. If there are domestic duties ahead of me, no writing happens. My piano stands silently accusing me of skipping another day to practice Chopin, although a lesson looms the next day. I ignore creative pleasures I hesitate to elevate to “need” status, because there are tasks ahead that improve the lives of others.  Top on the siren call would be perceived needs from my grandchildren and daughter. My granddaughter, a college senior, emails me a draft of her senior English thesis for editing. Her request leapfrogs to the top of my to-do list, real or imagined. I am flattered to be needed, especially to be needed for something that acknowledges I have a brain, not only a scrub brush.

Top on the siren call would be perceived needs from my grandchildren and daughter. My granddaughter, a college senior, emails me a draft of her senior English thesis for editing. Her request leapfrogs to the top of my to-do list, real or imagined. I am flattered to be needed, especially to be needed for something that acknowledges I have a brain, not only a scrub brush.

Her thesis has a reference to Mrs. Ramsey in Virginia Woolf’s To a Lighthouse. Married, and shrouded with the needs of her family, any creative vision Mrs. Ramsey might have is detoured through fulfilling family concerns. She knits socks, never quite finishing them. Juxtaposing Mrs. Ramsey is the unmarried Lily Briscoe who paints and completes a painting, Mrs. Ramsey’s domestic subservience to the needs of others shows a creative vision is impossible. Darning socks short circuits her visionary potential. I am considering that perhaps to be freely creative, a woman must be unshackled from family. On the other hand, an unmarried woman can be satisfied with fulfilling her own needs.

Would my mother’s life have been more creative had she not committed to a family? There is no way to know, but I am hoping she, like me, found enrichment in the creative imagination of thought, even in the sewing of quilts. For me, it would be ironing or kneading bread. For Mrs. Ramsey, as she knit, the narrative voice suggests a certain intelligence, a vision, so to speak. The reader has a sense of her visionary voice, however unfilled it might have been were she to complete a painting or write a novel.

The need to be needed may have hindered my creative life, or motivated it in inspiring me to be the most imaginative teacher I could be. Teaching itself is a creative act. With a filing cabinet stuffed with last year’s lesson plans, I recreated them each year. Although I may have been doing so to fulfill my students’ needs, I equally fulfilled my desire for change — delight in doing something different with certain literature I had taught several times.

For many women, the struggle continues in deciding whether we can live freely within a family structure. Perhaps the face-off of domestic duties and the poet within us creates an energized art that would not exist without the struggle. Deborah Levy quotes Audre Lorde in feeling that tension: “I am a reflection of my mother’s secret poetry as well as of her hidden angers”. (Audre Lorde)

A late September afternoon, I am walking home through Volunteer Park, past the playground, quiet as expectation now that children are back to school. Swings, slides, and sculptures for climbing stand silent midst a leaf-spotted lawn that borders Seattle’s historic Lakeview Cemetery. A chain link fence separates a high swinging child and rows of manicured tombstones, many erected in homage to the settlers who first populated our city with Gold Rush, timber-eager adventurers. Pausing before a limp swing lit with early autumn light, I am back seventeen years, lifting my toddler grandson into the swing, then swooshing the boy and swing for a high cemetery view. When both of us are ready to proceed to the slide, my grandson tells me, “I know, Nana, how all those people died.”

A late September afternoon, I am walking home through Volunteer Park, past the playground, quiet as expectation now that children are back to school. Swings, slides, and sculptures for climbing stand silent midst a leaf-spotted lawn that borders Seattle’s historic Lakeview Cemetery. A chain link fence separates a high swinging child and rows of manicured tombstones, many erected in homage to the settlers who first populated our city with Gold Rush, timber-eager adventurers. Pausing before a limp swing lit with early autumn light, I am back seventeen years, lifting my toddler grandson into the swing, then swooshing the boy and swing for a high cemetery view. When both of us are ready to proceed to the slide, my grandson tells me, “I know, Nana, how all those people died.” Well into my grandson’s nineteenth year, I have retold that story to my grandson and the entire family, so it is a chapter in our book of family humor and nostalgia. However, this morning, the passive swing not only reminds me of the funny story. I actually feel his three-year-old self is forever in that swing. Were he to ask, “Nana, push me,” I would not be surprised.

Well into my grandson’s nineteenth year, I have retold that story to my grandson and the entire family, so it is a chapter in our book of family humor and nostalgia. However, this morning, the passive swing not only reminds me of the funny story. I actually feel his three-year-old self is forever in that swing. Were he to ask, “Nana, push me,” I would not be surprised. Don’t tell me animals live only in the present with no vital memories. When it is time for us to go to our cottage, and we take out the cooler from the basement, our cats disappear. They know the cooler means travel, equals kitty carriers, equals confinement. We must put them in their carrier before even thinking of fetching the cooler. Yet remembering and simultaneous existence are not the same.

Don’t tell me animals live only in the present with no vital memories. When it is time for us to go to our cottage, and we take out the cooler from the basement, our cats disappear. They know the cooler means travel, equals kitty carriers, equals confinement. We must put them in their carrier before even thinking of fetching the cooler. Yet remembering and simultaneous existence are not the same. It circles around itself like a whirlpool in a pond, gathering newly dropped leaves as it turns. We are brought back around as we proceed forward. Have you heard the declaration, “I don’t want to go there?” I have. The sentence suggests a benefit to burying the past. Understood, as a way to avoid adversity, but today I am thinking that having lived through so many experiences with so many people, I am in a position to live in two or more places at once, and thus able to be more empathic with others who may be experiencing something for the first time.

It circles around itself like a whirlpool in a pond, gathering newly dropped leaves as it turns. We are brought back around as we proceed forward. Have you heard the declaration, “I don’t want to go there?” I have. The sentence suggests a benefit to burying the past. Understood, as a way to avoid adversity, but today I am thinking that having lived through so many experiences with so many people, I am in a position to live in two or more places at once, and thus able to be more empathic with others who may be experiencing something for the first time.

spread nets – as well as dodging ravenous seals a hundred pounds greater than the fish’s silvery weight, and the penetrating eyes of eagle and osprey from great heights.

spread nets – as well as dodging ravenous seals a hundred pounds greater than the fish’s silvery weight, and the penetrating eyes of eagle and osprey from great heights.  I lean precariously over the Little Quilcene Bridge and hold my camera steady, my back against the glare of early autumnal light, to capture the thrilling swish of a spawning pair. The shallows swirl around them in mock frenzy, river water splashing upwards like reverse rain.

I lean precariously over the Little Quilcene Bridge and hold my camera steady, my back against the glare of early autumnal light, to capture the thrilling swish of a spawning pair. The shallows swirl around them in mock frenzy, river water splashing upwards like reverse rain. They have parked their trucks along the road at the end of the bay and sloshed through the flats with fishing gear to snag the stragglers in the shallows. Determined to spawn, the fish have lost interest in feeding, ignoring any dangling bait, and thus victims only to snagging. Some sport.

They have parked their trucks along the road at the end of the bay and sloshed through the flats with fishing gear to snag the stragglers in the shallows. Determined to spawn, the fish have lost interest in feeding, ignoring any dangling bait, and thus victims only to snagging. Some sport.

Language changes faster than sunrise sets to dusk. Practice makes perfect. Besides, I am on board with the ways gender stereotypes control our thinking. More than fifteen years have passed since my church replaced old hymnals with new ones that removed gendered pronouns, yet that change doesn’t take easily with all. My voice raised in song, I often miss complete stanzas to an old hymn I thought I knew. All around me, I hear parishioners of my age stumble as they pray, “Our Father, our Mother . . .” Yet gradually God has changed from the great white man I envisioned in Sunday School, until God is now a spiritual wholeness with the feminine in me. Takes practice.

Language changes faster than sunrise sets to dusk. Practice makes perfect. Besides, I am on board with the ways gender stereotypes control our thinking. More than fifteen years have passed since my church replaced old hymnals with new ones that removed gendered pronouns, yet that change doesn’t take easily with all. My voice raised in song, I often miss complete stanzas to an old hymn I thought I knew. All around me, I hear parishioners of my age stumble as they pray, “Our Father, our Mother . . .” Yet gradually God has changed from the great white man I envisioned in Sunday School, until God is now a spiritual wholeness with the feminine in me. Takes practice. Similarly, the speaker peppered her commentary with “like” when there was no comparison intended that would call for “like.” Both the upspeak and “like” come from Valley Girl Talk, a dialect that connotes, for me, bikini clad California girls mostly interested in what they will wear to the next beach party. My granddaughter argues that “like” is the filler of her generation that allows the listener pause time to catch up; whereas in her grandparents’ generation is was “um.” Hmm.

Similarly, the speaker peppered her commentary with “like” when there was no comparison intended that would call for “like.” Both the upspeak and “like” come from Valley Girl Talk, a dialect that connotes, for me, bikini clad California girls mostly interested in what they will wear to the next beach party. My granddaughter argues that “like” is the filler of her generation that allows the listener pause time to catch up; whereas in her grandparents’ generation is was “um.” Hmm. Is the English language going to Hell in an I-Phone? The evolution of language is more than accepting new vocabulary. It is also accepting new tones and inflections. If we are lucky enough to converse with our grandchildren we can ride along.

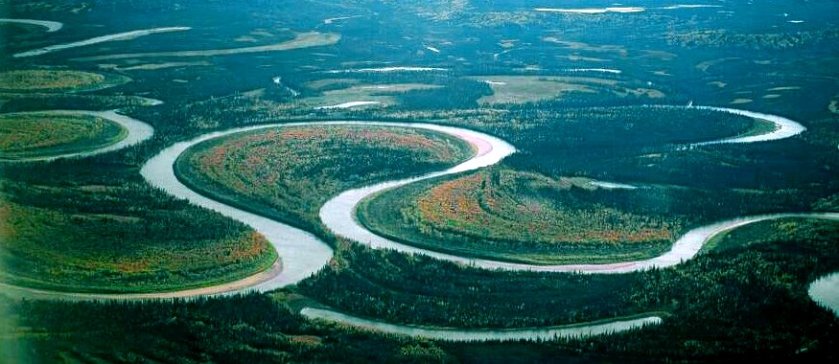

Is the English language going to Hell in an I-Phone? The evolution of language is more than accepting new vocabulary. It is also accepting new tones and inflections. If we are lucky enough to converse with our grandchildren we can ride along. Or maybe language does not change as a rapid-running creek into a stagnant pond, but rather a long, slow river, winding around like an ox-bow to the sea.

Or maybe language does not change as a rapid-running creek into a stagnant pond, but rather a long, slow river, winding around like an ox-bow to the sea.

Everyone laughed.

Everyone laughed. A young black woman raised her hand. “It is mostly older white people who say this,” she explained, “but I feel oppressed when people think they are flattering me by commenting on how articulate I am.” What she heard in that compliment, was “You are a black woman and so I am surprised that you speak so well.” The black man sitting next to her added he was tired of representing to others the conditions of a black man in America. “Just read the front page of your newspaper, if you want to know what it is like to be a black man in America. It is not the job of the oppressed to educate the oppressor.” Although that quotation came from one of our readings, hearing it from him, I heard it as Truth.

A young black woman raised her hand. “It is mostly older white people who say this,” she explained, “but I feel oppressed when people think they are flattering me by commenting on how articulate I am.” What she heard in that compliment, was “You are a black woman and so I am surprised that you speak so well.” The black man sitting next to her added he was tired of representing to others the conditions of a black man in America. “Just read the front page of your newspaper, if you want to know what it is like to be a black man in America. It is not the job of the oppressed to educate the oppressor.” Although that quotation came from one of our readings, hearing it from him, I heard it as Truth.

Then he began, in acute detail, to describe the sunrise over a semi-cloudy horizon above the Cascades. The scene called for his attention as we drove at 55 mph over the Ship Canal bridge. I remained attentive to cars ahead. Max described a ribbon of light between mountains and clouds, a “urine yellow beneath a black cape.” Mid-range, between Lake Union and the Cascades, he noted marshmallow clouds hovering at vacillating heights opening to reveal snow-spotted peaks. “ It seems even more dramatic,” he said, “because we are driving past.”

Then he began, in acute detail, to describe the sunrise over a semi-cloudy horizon above the Cascades. The scene called for his attention as we drove at 55 mph over the Ship Canal bridge. I remained attentive to cars ahead. Max described a ribbon of light between mountains and clouds, a “urine yellow beneath a black cape.” Mid-range, between Lake Union and the Cascades, he noted marshmallow clouds hovering at vacillating heights opening to reveal snow-spotted peaks. “ It seems even more dramatic,” he said, “because we are driving past.” We notice each new flowering dogwood tree or rose, pausing because we know the blossom will not last for weeks.

We notice each new flowering dogwood tree or rose, pausing because we know the blossom will not last for weeks. My generation sometimes boasts that it is The Greatest Generation and romanticizes cruising Route 66 in gas guzzling cars. Our generation paved miles of farmland for highways to take us to strip malls cemented over where valley farms once stood. Were we so inattentive to the environment we took for granted? Now we foresee a great debt called in for our children and grandchildren to pay.

My generation sometimes boasts that it is The Greatest Generation and romanticizes cruising Route 66 in gas guzzling cars. Our generation paved miles of farmland for highways to take us to strip malls cemented over where valley farms once stood. Were we so inattentive to the environment we took for granted? Now we foresee a great debt called in for our children and grandchildren to pay. Especially in Seattle, they are aware that student housing costs as much as their tuition, in a city where the two richest men in the world live in mansions. Unlike our generation, these young adults do not expect to surpass the prosperity of their parents. As Max focused on the beauty of a sunrise, they are paying attention to climate change and the very air they breathe.

Especially in Seattle, they are aware that student housing costs as much as their tuition, in a city where the two richest men in the world live in mansions. Unlike our generation, these young adults do not expect to surpass the prosperity of their parents. As Max focused on the beauty of a sunrise, they are paying attention to climate change and the very air they breathe.

No matter what tasks we are doing, we stop to run through the open gate and plunge in for a swim, push out in a kayak. or balance on a paddle board as soon as a chart in that book registers eight feet or more. Winters, the high tides can exceed 13 feet, and when married to high winds, the sea trespasses, often knocking out the gate with a floating log, white caps swamping our lawn.

No matter what tasks we are doing, we stop to run through the open gate and plunge in for a swim, push out in a kayak. or balance on a paddle board as soon as a chart in that book registers eight feet or more. Winters, the high tides can exceed 13 feet, and when married to high winds, the sea trespasses, often knocking out the gate with a floating log, white caps swamping our lawn.

“I love the low tide, as much as the high tide,” he said, reaching for the binoculars to spot heron tiptoeing between the streams and the violet green swallows checking out the boxes he has raised on poles along the shore.

“I love the low tide, as much as the high tide,” he said, reaching for the binoculars to spot heron tiptoeing between the streams and the violet green swallows checking out the boxes he has raised on poles along the shore.

Changing tides inspire humility, helping me to accept what gifts I didn’t know were coming. Just as high winter tides carry a battering ram of a tree trunk to wipe out our driftwood fence, so the water retreats, dumping our fence and stairs at the end of the bay. Neighbors help us retrieve what is ours, and in our scavenging, we find even better planks for restoration. Low tides uncover oysters and clams: a table-is-set ebbing of culinary fame. Even baby crabs scramble along the shore. In late August, salmon return along the streams that lace the flats. Salmon battle determinedly up those streams between lines of families fishing for a big one to take home for dinner. The tides give and take away, like the hand of a natural god.

Changing tides inspire humility, helping me to accept what gifts I didn’t know were coming. Just as high winter tides carry a battering ram of a tree trunk to wipe out our driftwood fence, so the water retreats, dumping our fence and stairs at the end of the bay. Neighbors help us retrieve what is ours, and in our scavenging, we find even better planks for restoration. Low tides uncover oysters and clams: a table-is-set ebbing of culinary fame. Even baby crabs scramble along the shore. In late August, salmon return along the streams that lace the flats. Salmon battle determinedly up those streams between lines of families fishing for a big one to take home for dinner. The tides give and take away, like the hand of a natural god. If it is a Low – Low, I may forget that there ever were welcoming waves in front of our cottage. If it is a high tide day, I know I am riding a surface on a paddle board, head-high enjoying the sunset sink behind Mt. Townsend. Most days are those Low Highs or High Lows, but nothing is stagnant. All life is movement. We know the moon will turn from crescent to full, and the bay that emptied all but bubbling craters where clams breathe, will within hours, cover meandering streams with salt and sea.

If it is a Low – Low, I may forget that there ever were welcoming waves in front of our cottage. If it is a high tide day, I know I am riding a surface on a paddle board, head-high enjoying the sunset sink behind Mt. Townsend. Most days are those Low Highs or High Lows, but nothing is stagnant. All life is movement. We know the moon will turn from crescent to full, and the bay that emptied all but bubbling craters where clams breathe, will within hours, cover meandering streams with salt and sea.

Barack Obama based his drive to the presidency not on a slogan to “Make America Great Again”, but on hope. The Barack Obama “Hope” poster is an image of President Barak Obama. The image, designed by artist Shepard Fairey, was widely described as iconic.

Barack Obama based his drive to the presidency not on a slogan to “Make America Great Again”, but on hope. The Barack Obama “Hope” poster is an image of President Barak Obama. The image, designed by artist Shepard Fairey, was widely described as iconic.

Archibald MacLeish writes in Ars Poetica, “For all the history of grief / An empty doorway and a maple leaf.” What profound absence he expresses in one metaphorical image, so that my heart hollows out with sadness as I picture that open doorway beyond which there is absence. In defining grief, a dictionary would settle for “deep, sadness, often lasting a long time.” The dictionary is accurate enough but cannot replicate the feeling of grief defined in MacLeish’s open door or the falling maple leaf.

Archibald MacLeish writes in Ars Poetica, “For all the history of grief / An empty doorway and a maple leaf.” What profound absence he expresses in one metaphorical image, so that my heart hollows out with sadness as I picture that open doorway beyond which there is absence. In defining grief, a dictionary would settle for “deep, sadness, often lasting a long time.” The dictionary is accurate enough but cannot replicate the feeling of grief defined in MacLeish’s open door or the falling maple leaf. Many Americans have left religion altogether because the Bible remains the cornerstone of churches, and in an empirical age, people will not subscribe to a belief in miracles such as virginal birth. Others, in some fundamentalist churches, turn off the reality button, permitting their literalism to deny what science disproves. The Bible itself abounds in contradictions, making “the word of God” as evasive as mercury spilled from a broken thermometer. For me, literal readings can make the Bible as shallow as a puddle in which we look no deeper than the reflection of our own face. Metaphorical readings expand in lakes and oceans, often feeding channels between islands no one mapped.

Many Americans have left religion altogether because the Bible remains the cornerstone of churches, and in an empirical age, people will not subscribe to a belief in miracles such as virginal birth. Others, in some fundamentalist churches, turn off the reality button, permitting their literalism to deny what science disproves. The Bible itself abounds in contradictions, making “the word of God” as evasive as mercury spilled from a broken thermometer. For me, literal readings can make the Bible as shallow as a puddle in which we look no deeper than the reflection of our own face. Metaphorical readings expand in lakes and oceans, often feeding channels between islands no one mapped.  Christ does not have to resurrect in the flesh, offering his wounds to Thomas or anyone else in doubt. Christ can “come again,” among his followers who, despairing his death, realize his teachings never left them, but will endure. Christ had risen!

Christ does not have to resurrect in the flesh, offering his wounds to Thomas or anyone else in doubt. Christ can “come again,” among his followers who, despairing his death, realize his teachings never left them, but will endure. Christ had risen! These are facts about Ms. Obama’s life there, but it was her metaphorical descriptions of her life from the South Side of Chicago to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue that helped me to feel what she felt. Metaphor opens the envelope for empathy. What a wonderful organ our brain is that we can look at the moon while Alfred Noyes describes “the moon is a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas,” and we can see a full sail sailing ship in rough seas and at the same time a real moon, flitting in a tumultuous dance among clouds.

These are facts about Ms. Obama’s life there, but it was her metaphorical descriptions of her life from the South Side of Chicago to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue that helped me to feel what she felt. Metaphor opens the envelope for empathy. What a wonderful organ our brain is that we can look at the moon while Alfred Noyes describes “the moon is a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas,” and we can see a full sail sailing ship in rough seas and at the same time a real moon, flitting in a tumultuous dance among clouds.